Big Tech is Trying to Burn Privacy to the Ground–And They’re Using Big Tobacco’s Strategy to Do It

Page Media

This article originally appeared on Tech Policy Press.

With the looming presidential election, a United States Supreme Court majority that is hostile to civil rights, and a conservative effort to rollback AI safeguards, strong state privacy laws have never been more important.

But late last month, efforts to pass a federal comprehensive privacy law died in committee, leaving the future of privacy in the US unclear. Who that future serves largely rests on one crucial issue: the preemption of state law.

On one side, the biggest names in technology are trying to use their might to force Congress to override crucial state-level privacy laws that have protected people for years.

On the other side is the American Civil Liberties Union and 55 other organizations. We explained in our own letter to Congress how a federal bill that preempts state law would leave millions with fewer rights than they had before. It would also forbid state legislatures from passing stronger protections in the future, smothering progress for generations to come.

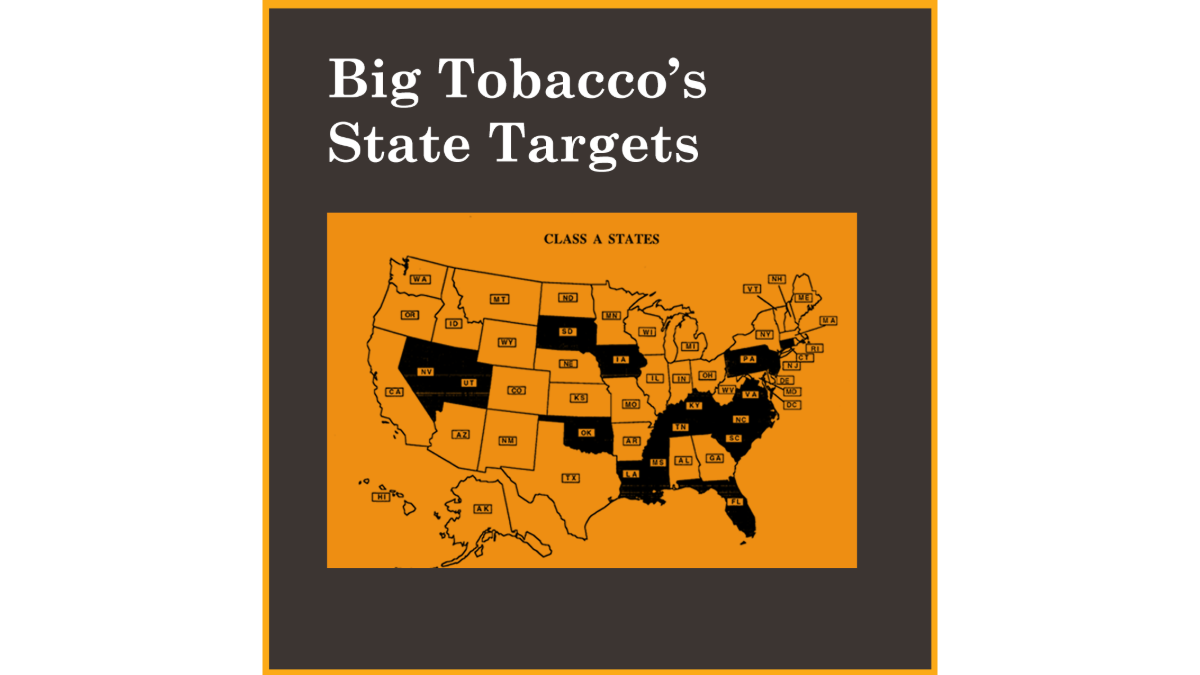

Preemption has long been the tech industry’s holy grail. But few know its history. It turns out, Big Tech is pulling straight from the toxic strategy that Big Tobacco used in the 1990s. Back then, Big Tobacco invented the “Accommodation Program,” a national campaign ultimately aimed at federal preemption of indoor smoking laws.

Phillip Morris and others in the tobacco industry implemented a three-step strategy which is only known through documents made public in litigation years later. Those documents reveal the inner workings of a nefarious corporate influence machine designed to quietly snuff out a democratic movement that threatened their profits. And now Big Tech is trying to do the same.

But it’s not too late. We can ensure our civil rights and civil liberties are protected in the digital age. But to defeat Big Tech’s strategy, first we must understand it.

Step one: Respond to a PR crisis with a flood of deceptive bills.

Big Tech is facing a public relations crisis, just like Big Tobacco did over thirty years ago.

Public opinion has turned against the tech industry. A 2021 poll of confidence in American institutions put Meta as the “least trusted” institution. Other tech titans, like Amazon and Google, also have experienced steep declines in public confidence.

Trust is eroding because the public has woken up to the harms of the surveillance business model. Tech companies have mined massive amounts of personal information about who we are, where we go, what we do, and who we know. They’ve enabled micro-targeting that preys on seniors and the financially vulnerable, supercharges police surveillance, and helps power the federal deportation system. The tech industry has built algorithms that determine who has access to housing, credit, employment, insurance, and healthcare in ways that can exacerbate racial and economic disparities. It has developed face surveillance technology that profits off racially biased policing and incarceration, enabled scammers to proliferate, and pushed low-quality, overpriced junk on consumers.

The tobacco industry faced similar public backlash following the US Surgeon General’s groundbreaking 1986 report that highlighted the health risks of secondhand smoke. A fierce grassroots movement notched early victories, including the Beverly Hills smoke-free restaurant ordinance and Pittsburgh’s restriction on smoking in public places. As these protections spread, tobacco executives recognized that the growing movement could cost billions in lost profits and developed comprehensive plans to ward off community action and protect their business model.

Comprehensive plans from the time show tobacco companies unleashing an arsenal of front groups, making donations to pro-tobacco candidates, recruiting local businesses, hiring lobbyists, and spending heavily to produce laws that undermined public health and protected the industry’s profits, with a devastating human cost.

In place of smoking bans, the tobacco industry pushed ineffective alternatives that only pretended to address the issue. Chief among them were non-smoking sections, which, of course, continued to allow smoking, and filled the air with secondhand smoke.

By 1995, 17 states, including leading tobacco producer Virginia, had passed what Big Tobacco considered model legislation. Among the worst of these was Virginia’s “Indoor Clean Air Act,” deliberately designed—and deceptively named—to extinguish the growing energy around city-level anti-smoking laws.

Skip to today, and Big Tech is pursuing the same approach, often in the same states.

They too have funded front groups, hired an armada of lobbyists, donated millions to campaigns, and opened a firehose of lobbying money to replace real privacy laws with fake industry alternatives as ineffective as non-smoking sections.

In response to privacy laws passed at the state and local level, Big Tech dramatically escalated its lobbying. The seven largest tech companies spent nearly $70 million in 2021, then set new spending records in 2022, 2023, and likely 2024.

All that cash has paid off. There has been “a coordinated, nationwide campaign by Big Tech to mold the rules to its will.” In 2021, Virginia lawmakers rammed through the “Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act” a law provided by an Amazon lobbyist—predictably, it was “just what Big Tech wants”.

By May 2024, tech had leveraged its money and influence to pass industry-favorable privacy laws in numerous states.

Step two: Point to the “patchwork.”

With the board set, Big Tech can now move onto step two of the Tobacco strategy: use the ineffective laws they created as leverage to eliminate the good laws in other states.

Tech lobbyists love to complain about the "patchwork”—meaning diverse state privacy laws. It’s the tech industry’s favorite talking point. They even created a website called “United for Privacy: Ending the Privacy Patchwork.” Google, Amazon, and Meta all used to be listed on the partners page, but have now been removed.

In 2022, industry front groups co-signed a letter to Congress arguing that “[a] growing patchwork of state laws are emerging which threaten innovation and create consumer and business confusion.” In 2024, they were at it again this Congress, using the term four times in five paragraphs.

Big Tobacco did the same thing. They pushed op-eds arguing that a “patchwork of local laws is no way to fight smoking.” They paid for studies that examined the economic impact that a “patchwork of local smoking ordinances” can have on chain restaurants. And they provided industry mouthpieces with talking points calling local smoking laws “confusing patchwork quilt.”

Let’s be clear: Big Tech is crying crocodile tears. Other companies regularly comply with a wide variety of different state provisions in other areas of the law.

Step three: Use preemption to kill the grassroots movement.

[T]he Tobacco Institute and tobacco companies’ first priority has always been to preempt the field, preferably to put it all on the federal level, but if they can’t do that, at least on the state level.

Victor L. Crawford, Former Tobacco Institute Lobbyist, Journal of the American Medical Association, 7/19/95

The final step for Big Tobacco then, and Big Tech now, is to use preemption to erase state laws and curb a state’s ability to pass new, stronger laws in the future.

Today, many federal lawmakers want to do the right thing and pass long overdue protections governing privacy, artificial intelligence, and civil rights. But if lawmakers endorse preemption, they are making a deal with the devil that will ultimately sabotage the future of privacy in the United States.

Make no mistake, we must have strong federal privacy laws. But preemption plays right into the hands of Big Tech. Federal law should establish a foundation that cities and states can build on, not a ceiling blocking all future progress.

Once state legislatures are sealed, power decreases dramatically for grassroots activists, communities of color, and other groups that have limited access to the halls of Congress and far fewer resources to make their voices heard.

Cities and states are nimbler than Congress, and historically are where real change begins. In 1972, California enshrined a right to privacy in the state constitution that offers powerful protections against modern privacy abuses. In 2008 Illinois passed the Biometric Information Privacy Act, which recently resulted in a $650 million settlement against Facebook. In 2019, the ACLU of Northern California led a coalition effort to pass San Francisco’s facial recognition ban—a first in the nation that sparked a wave of similar laws throughout the country. And most recently, Washington state and Maryland passed privacy legislation that will be among the nation’s strongest.

Phillip Morris never succeeded in passing a federal law that preempted states’ ability to pass anti-smoking laws. Congress held strong then, and needs to do the same now.

We deserve a future where technology works for us, not against us. And for that to happen, we must all fight to keep preemption off the table.