Cops Blanketed San Francisco In Geofence Warrants. Google Was Right to Protect People's Privacy

Page Media

In the final weeks of 2023, Google announced a change that may eliminate a problematic practice that allows police to surveil entire communities. The change appears to place significant limits on law enforcement’s ability to use “geofence warrants” (also called “reverse location search warrants”) to find out who was in a particular place at a particular time. Google’s announcement is welcome news, and we are cautiously optimistic that this change—once it rolls out—will protect people for years to come.

Police use of geofence warrants has long been cloaked in secrecy. We know thousands of warrants have been issued, but the particular locations searched—and, more importantly, the people and communities targeted—have long been unknown, either buried in government files that are difficult to access or subject to overly broad efforts to keep the extent of surveillance technology secret from the public.

Over the last year, the ACLU of Northern California has conducted an extensive investigation into the use of geofence warrants by law enforcement in San Francisco. Working with a team of UC Berkeley law students, we spent hundreds of hours reviewing thousands of warrants in person at the San Francisco Criminal Court. We analyzed geofence warrants issued from January 2018 to August 2021 and compiled records of where police used them, and who was potentially affected.

Our investigation likely unearthed only a fraction of the geofence warrants used in San Francisco. But the reach of even the warrants we reviewed is striking, particularly in such a densely populated urban area. Our analysis shows that reverse-location search warrants reached hundreds of homes, apartment buildings, sites of medical care, busy thoroughfares, bars and restaurants, hotels and conference centers, and places of worship. Our results offer a glimpse into how this kind of surveillance technology operates in real-world scenarios.

Geofence Warrants Vastly Expand Police Search Powers

Reverse-location searches are at odds with the longstanding principle that government agents cannot conduct generalized searches. Reverse-location searches allow police to tap into Google’s store of location information to demand information on devices that were in a geographical region at a particular time. Unlike traditional warrants, which require police to describe what is to be searched for and seized, a geofence warrant targets an area and then identifies suspects by sifting through an enormous repository of location information.

In 2020, Google released a fact sheet revealing that geofence warrants constituted more than 25% of the company’s warrant requests in the United States and that law enforcement in California had submitted more dragnet surveillance demands than any other state.

A Closer Look

Our analysis of a warrant near Lower Nob Hill is one example of how geofence warrants infringe on our civil liberties. The warrant boundary is mere blocks away from two healthcare clinics that have long provided reproductive care to people in San Francisco. Imagine that you or your loved one visited one of these centers to seek support. You assumed this was a private health matter, but by visiting one of these healthcare providers when a geofence warrant was issued, your movements may have been captured and shared with law enforcement. This type of dragnet surveillance has far-reaching implications in a world where abortion rights are under attack.

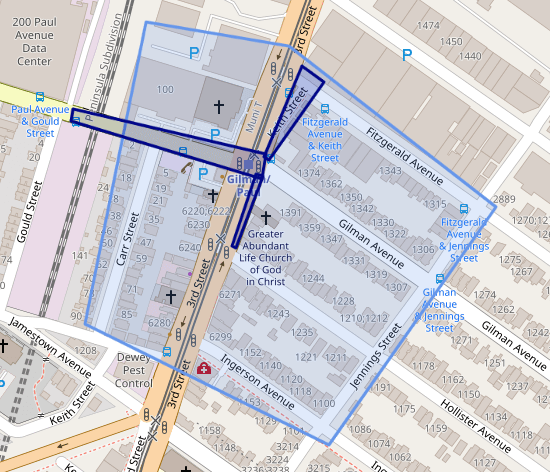

Geofence warrants are, by nature, massively overbroad. Law enforcement may be interested in a single suspect, and in trying to identify them, request a geofence warrant that covers blocks of homes, offices, and other private spaces. For example, a single warrant we analyzed in San Francisco's Bret Harte neighborhood captured four places of worship, including Cornerstone Missionary Baptist and Evergreen Baptist Church. If you went to one of these churches during a window in which a geofence warrant was issued, law enforcement could have discovered where you were and who you were with.

Figure 1. Geofence warrant issued in San Francisco's Bret Harte neighborhood

The same logic applies to hotels, restaurants, and shopping centers. You might have believed your stay at Le Méridien (a luxury hotel in Downtown San Francisco that has since been renamed) was private, but you can't shield yourself from dragnet surveillance. One geofence warrant issued on a Friday evening captured all of Le Méridien hotel, Umpqua Bank, Far East National Bank, Cathay Bank, and other commercial landmarks. Whether you were in your hotel room or grabbing a salad at Mixt Greens on Commercial Street—with no connection at all to any criminal activity—your location information might well have been shared with the police.

Figure 2. Geofence warrant issued in downtown San Francisco

Geofence Warrant Errors Cast a Miles-Wide Surveillance Net

Geofence warrants, like all other warrants, are not error-proof. During our investigation, we discovered one warrant that apparently contained an alarming error.

The error (perhaps the result of a typo) resulted in a warrant stretching nearly two miles across San Francisco and permitted law enforcement to capture information about people across the United Nations Building, Asian Art Museum, Civic Center Courthouse, State of California Building, Rosa Parks Senior Center, and Fire Station 5. Many private homes were also captured in the massive sweep.

Figure 3. Geofence warrant spanning two miles

If our review revealed an error, how many other mistakes exist in the thousands of requests received and granted by Google?

A Summary of Our Findings

We conducted a high-level analysis of the types of places captured by law enforcement in geofence warrants across San Francisco. Note that this list only includes sites within or immediately bordering the area of a reverse-location search. People in transit, or simply walking down the street, could also have been swept up in the police’s dragnet surveillance. Even people in the presumed privacy of their own homes could have been located and monitored by law enforcement. This is a troubling violation of our right to be secure in our homes and to be free from unreasonable search without probable cause.

- Hundreds of places where people live. The warrants in our investigation revealed 121 homes and 82 apartment buildings covered by geofence warrants.

- 84 places where people work. The warrants we found covered numerous places where people work, including software companies (Oracle), consulting firms (AECOM), law firms, investment services companies (New Island Capital Management), nonprofit organizations (Horizons Foundation), and architecture firms (FORGE Architecture & Design).

- 32 bars and restaurants. The warrants covered numerous places where people eat, drink, and gather, including The Barrel Room, Wildflower Cafe, Irish Times, Morning Brew Coffee & Tea, Tlaloc Sabor Mexicano, Peet’s Coffee, Mixt, Wayfare Tavern, Leo’s Oyster Bar, Wexler’s, Big Night Restaurant Group, Starbucks, Jackalope, Piroo, Mustafio’s Pizza, Wen’s Kitchen, Alegrias, Marina Sushi Bar, Montecristo, B&J Burgers, Marengo on the Alley, The Club at Wingtip, Ladle & Leaf, Il Canto Cafe, All Day Kitchens, The Landing, King Sun Buffett, Deck the Halls, The Dorian, Nippon Curry, Westwood, and Tijuana Taquero Outlaw Kitchen.

- 12 places of worship. The warrants in our investigation covered numerous places where people of all different faiths worship, including Al Tawheed Mosque, Evergreen Baptist Church, San Fran Community Church, Cornerstone Missionary Baptist, Greater Abundant Life Church, New Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church, Iglesia del Príncipe De Paz, Immaculate Conception Ukrainian Catholic Church, Bayview Baptist Church, All Hallows Roman Catholic Church, New Liberation Presbyterian Church, and Saint John the Baptist Serbian Orthodox Church.

- 7 medical sites of care. The warrants in our investigation covered numerous places where people might seek medical care, including One Medical, Kaiser Permanente Medical Center, Arthur H. Coleman Medical Center, Bayview Health & Wellness Center, and Good Shepherd Gracenter.

- 5 grocery stores. The warrants in our investigation covered numerous places where people shop for essential goods, including New India Bazar, S & B Grocery & Liquor Store, Post & Polk Convenience Store, Halal Green Apple Market, and Fords Grocery.

- 5 event spaces or rooms. The warrants in our investigation covered numerous event spaces, including large convention venues, such as South San Francisco Conference Center, and smaller community hubs, such as Bayview Opera House.

- 4 recreational spaces. The warrants in our investigation covered numerous recreational spaces that serve diverse San Francisco communities, including Rosa Parks Senior Center, Joseph Lee Recreation Center, Mary Hellen Rogers Senior Community, and Community Youth Center of San Francisco.

- 7 schools and daycares. The warrants in our investigation covered numerous schools, including Golden Bridges School, Leola M. Havard Early Education School, Tule Elk Park Child Development Center, and Civic Center Secondary School. The warrants also covered daycares, including Dong Dong Home Day Care, Mi Escuelita en Español, and Janet's Family Childcare.

Surveillance of Marginalized Communities

Our analysis revealed geofence warrants used across San Francisco, but certain neighborhoods were more impacted than others. For example, a significant percentage of the warrants were targeted in or around Portola, an immigrant-heavy neighborhood with a household income nearly $30,000 lower than the entirety of San Francisco. Portola residents identify as 47.8% Asian, 14.9% Hispanic or Latino, and 6.2% Black. Non-U.S.-born citizens account for 40.6% of the population, and another 13.6% consists of non-citizens.

This is another example of how law enforcement disproportionately targets marginalized communities with surveillance, causing harm to people who are low-income or people of color.

In Conclusion

Google’s move is a positive step, but we must remain vigilant. We must continue to scrutinize the use of technology by law enforcement to ensure it aligns with our values of privacy, equity, and justice. A critical example of this is Proposition E, a measure on the March 2024 San Francisco ballot that would curtail police accountability and massively expand secret police surveillance in the city without safeguards to prevent abuse. Technology should be put to work to help people, not track their every move. And, when surveillance technology is used, it must be subject to public oversight.

*We’d like to thank Katherine Wang, Pierce Stanley, and Emma Lurie, former interns with the ACLU of Northern California, as well as the following members of UC Berkeley School of Law’s Digital Rights Project: Noor Alanizi, Chiagoziem Mark Aneke, Marian Avila Breach, Tiffaney Boyd, Owen Cooper, Anan Hafez, Paul Hsu, Sohaima Khijli, Madison Lee, Jessica Lynn, Nina Perez-Morales, Andrea Sotelo Gasperi, Meredith Sullivan, Emily Welsch, and Nikita Zhu.