Enough Is Enough: Poor Women Are Not Having Babies for Money

Page Media

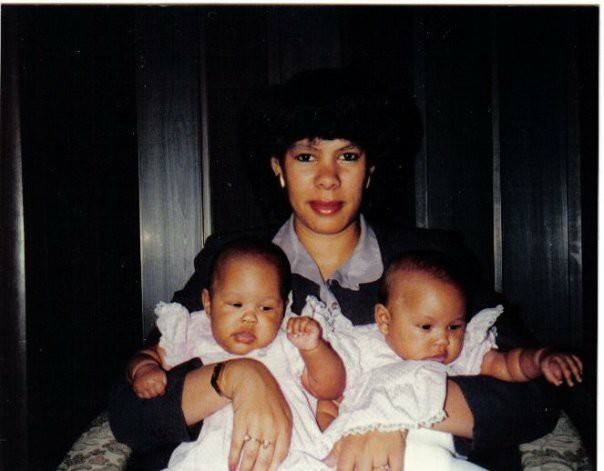

When I was young, my mom was on welfare. She wasn’t unlike other moms on our South Los Angeles block: single, working multiple jobs, and doing her best to keep her head above water. She cared deeply for my brother, my sister, and me. We knew she did, because in order to make sure we had enough, my mom braved the stigma that—then and now—is tethered to receiving state benefits. Braving it is what poor people do.

Despite that, like other families living below the federal poverty line, my family was punished for being poor. Back then it was all about shaming—from policy makers, from moral demagogues, and from other poor people. It was ubiquitous. Today the shaming still persists, but with it has come a divestment in resources. In 1994, California—a state that has long touted its leadership in eradicating poverty—instituted the Maximum Family Grant rule. This rule denies financial support to babies born while their families are receiving grants from CalWORKs, California’s welfare program. This is less policy than social experiment—one based on the deeply problematic notion that if the state deprives families of critical resources for newborn babies, those families will stop reproducing. In reality, it simply punishes poor women for their reproductive decisions and pushes families further into poverty.

This year advocates are working hard to repeal the Maximum Family Grant rule, ensuring every child born into a family receiving benefits, no matter their birth order, has equal protection against the short- and long-term effects of poverty. With support from both reproductive justice and anti-poverty advocates, state Sen. Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles) introduced SB 899 to repeal the Maximum Family Grant rule and reinforce that a child born into poverty isn’t less deserving than one who is not born into such circumstances.

But advocates are facing a heavy lift. Passing this legislation means investing more than $200 million in CalWORKs families. It also means deconstructing the narrative that poor women have babies for money and making the case that every person, no matter their income, deserves to parent their children with dignity. Opponents argue that people should simply wait to have children until they can afford to do so. But the Economic Mobility Project study conducted by the Pew Research Center found that 70 percent of people who are born into poverty never leave poverty. Is the presumption that those people should never have children?

I remember, vaguely, the shaming energy on my block as a child. But there was something more sinister that left a bad taste in all of our mouths: There was a permeating assumption that the women in my community who were receiving benefits were “gaming the system,” that they collected benefits and never worked. I never met someone who did that. Our neighbors—who, like us, were poor enough to qualify for benefits—all worked. If they didn’t get up to go to a nine-to-five job, they worked from home. They cooked all day and sold plates of food to other families or people passing by. They did hair in their kitchen or watched another family’s kids. They picked up recycling and trudged it to the recycling center for pennies. They worked.

The Maximum Family Grant rule punishes poor women, many of whom are women of color. Initially welfare recipients were mostly white widows or “deserving” divorced women. When the program was conceived, Black women were ineligible to receive aid because they, in the words of Dorothy Roberts, “were considered inappropriate clients of a system geared to unemployable women.” At that time there was little criticism of the program. When Black women became eligible, due in large part to the Civil Rights movement, the program drew public ire. White women were given the benefit of the doubt while other women, Black women especially, were judged much more harshly for their sexual and reproductive choices.

In her book, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty, Roberts writes, “Black mothers’ inclusion in welfare programs once reserved for white women soon became stigmatized as dependency and proof of Black people’s lack of work ethic and social depravity. The image of the welfare mother quickly changed from the worthy white widow to the immoral Black welfare queen. … Part of the reason that maternalist rhetoric can no longer justify public financial support is that the public views this support as benefiting primarily Black mothers.”

The Maximum Family Grant rule includes some exceptions that force a woman to choose between receiving aid to feed and clothe her family and disclosing personal medical information. If a child is conceived due to rape or incest, a mother must prove it by disclosing her status as a survivor. The only other exemptions are for the failure of highly invasive long-acting contraceptive methods that are designated by the state. The Maximum Family Grant rule undermines the intended mission of CalWORKs to provide temporary support to low-income families; it also limits women’s reproductive decisions and leads to government intrusion into families.

We know that not everyone in this country can earn at the same level, but Californians, among others, have long believed that it is not the government’s place to determine when and how a family grows. California has a long history of supporting a woman’s personal decisions regarding her reproductive choices. This should be true for all women, no matter their income.

Receiving aid helped my mom stay afloat. She needed help for a little while, and even though there was shame attached to that, she did it because she cared deeply about the well-being of her kids. Reproductive justice means honoring a person’s right to parent their children with dignity. Repealing the Maximum Family Grant rule will not lift families out of poverty entirely, but it will get us one step closer to that goal.

Shanelle Matthews is the Communications Strategist at the ACLU of Northern California.