Know Your History? The ACLU of Northern California, Protecting Your Rights for Decades - #ACLUTimeMachine

Page Media

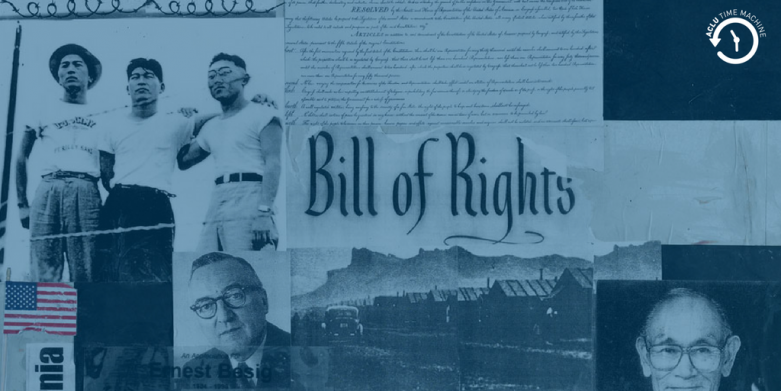

At a time when the internment of Japanese-American citizens has been cited as precedent for creating a Muslim-American registry, flag burning is mentioned casually as something that might strip Americans of citizenship, and the Constitution feels under attack, want to know more about the history of the ACLU?

The ACLU of Northern California was founded in 1934. During these 80+ years, the ACLU-NC has brought Japanese-American internment and other injustices all the way up to the Supreme Court, working to protect the rights of Californians — whatever the challenge.

The late Edison Uno, an ACLU-NC Board member and World War II internee, said:

We may have eliminated the statutory provisions for detention camps, but we must always remember it takes eternal vigilance to improve democracy.

always remember it takes eternal vigilance to improve democracy.

The ACLU of Northern CA through the decades...

By: Elaine Elinson and Stan Yogi

In 1934, one of the most dramatic labor struggles in United States history took place in San Francisco. To gain union recognition and improve the notoriously bad working conditions on the waterfront, Bay Area maritime workers went on strike.

After vicious police attacks, culminating in “Bloody Thursday” (July 5, 1934) when two trade unionists were shot and killed outside the union hall at Steuart and Mission Streets, a general strike was called to support the longshoremen.

Governor Frank Merriam called in National Guardsmen who posted themselves on top of the Ferry Building with machine guns. Police and vigilante groups attacked union halls, strike kitchens and laborers’ homes with tear gas, bullets and bricks.

The national ACLU, then 14 years old and based in New York, sent two southern California organizers, Ernest Besig and Chester Williams, to help combat the wholesale attack on the workers’ civil liberties.

They recruited the first ACLU-NC Board of Directors from local civic leaders, including philosophy professor Dr. Alexander Meiklejohn, poet Helen Salz and UNESCO Director Dr. Charles Hogan, who was elected chairperson. Their initial meeting, on September 21, 1934 in the Bellevue Hotel in San Francisco, drew 60 members.

One of the ACLU-NC’s first actions was to sue San Francisco and Oakland for not protecting strikers’ First Amendment rights. The new organization was successful.

Labor issues continued to dominate the early years of our affiliate. When the 1935 Holmes-Eureka lumber strike broke out, three pickets were killed, eight wounded and more than 150 arrested. No attorney in Humboldt County was willing to defend the strikers, so the ACLU-NC offered legal counsel.

Besig planned to be in Eureka for 30 days. But those 30 days extended to a lifetime of service to the ACLU. He was Executive Director of the affiliate until 1971.

The fledgling organization procured full pardons for 22 Wobblies (members of the International Workers of the World) who had been convicted under California’s criminal syndicalism law, which outlawed membership in radical groups. The ACLU-NC aided in the defense of Tom Mooney and Warren Billings, San Francisco labor leaders falsely convicted of bombing San Francisco’s 1916 Preparedness Day Parade. After a massive international campaign for their release, the two were pardoned; they had served more than 20 years in San Quentin.

The affiliate also successfully challenged California’s “anti-Okie” laws, which made it a crime to help an indigent person enter the state.

The affiliate took up other First Amendment issues as well. Throughout the decade, the organization defended Jehovah’s Witness students who were suspended for not saluting the flag. These were the first of many freedom of religion cases that the affiliate later undertook on behalf of Black Muslims, Jews, Sikhs, Buddhists and other religious minorities.

The outbreak of World War II brought new challenges for the ACLU-NC. Carrying on the tradition of the national ACLU, which was founded to defend conscientious objectors (COs) during World War I, the ACLU-NC fought for the rights of COs, including atheists who opposed the war on moral, as opposed to traditional religious, grounds. The affiliate also sued on behalf of peace groups to use public facilities for meetings and anti-war rallies.

But one of the proudest episodes of ACLU-NC history was our challenge to the wartime relocation and forced detention of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans. In 1942, San Leandro draftsman Fred Korematsu was jailed for refusing to obey military orders that all Japanese Americans report to relocation centers.

The ACLU-NC represented Korematsu all the way up to the United States Supreme Court, arguing that the exclusion and detention laws violated basic constitutional rights. But in 1944, the high court upheld Korematsu’s conviction and the wartime measures on the grounds of military necessity. It took four decades, intensive research, and a team of lawyers led by the children of internees to have Korematsu’s conviction overturned by U.S. District Court Judge Marilyn Hall Patel in 1983.

ACLU-NC Executive Director Besig also investigated and exposed the “Gestapo-like” conditions at the camp at Tule Lake often at great physical danger to himself.

The national ACLU disagreed with the affiliate’s strong stance against the internment and urged our affiliate to drop its representation of Korematsu. Besig refused.

The ACLU-NC was also one of the early fighters against race discrimination in the state, challenging the segregation of Mexican Americans and blacks in schools, swimming pools and other public facilities. The ACLU mobilized support for African American sailors at Port Chicago who refused to load munitions ships after an explosion killed 300 and injured hundreds more. Though the sailors were court-martialed and imprisoned, their action eventually led to the desegregation of the Navy.

The end of the war presented new dangers for civil liberties as the Cold War on the home front gave rise to a new era of political repression.

The ACLU-NC defended hundreds of victims of federal and state “loyalty and security” programs, and led opposition to the witch-hunting of congressional and state legislative “Anti-American” committees.

Against all odds during the Red Scare, the ACLU-NC challenged a wide variety of loyalty oaths: from one required of recipients of unemployment benefits, to the Levering Act that mandated oaths from all California public officials and state employees.

After the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) held widely publicized hearings in San Francisco where labor leaders refused to testify and protestors were hosed down the steps of City Hall by police, HUAC released a distorted propaganda film, Operation Abolition. In a counter-attack that was way ahead of his time, Besig produced a nationally-distributed film refutation, Operation Correction, which methodically revealed HUAC’s distortions and lies.

The ACLU-NC defended Eastern European and Chinese immigrants who faced deportation for their political views, as well as U.S. citizens who were denied passports because they were deemed “security risks,” among them poet Gary Snyder.

In 1957, Lawrence Ferlinghetti was put on trial for selling copies of poet Allen Ginsberg’s Howl at his new San Francisco bookstore, City Lights. The ACLU-NC defended Ferlinghetti against charges of “obscenity,” and the successful outcome set a new course for artistic expression. At the 50th anniversary of the bookstore, Ferlinghetti told the crowd, “If it hadn’t been for the ACLU, we’d have been out of business forever.”

The ACLU-NC aided the growing civil rights movement by providing legal counsel for campaigns by African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and Asian Americans to organize and speak out against racism in housing, education and employment.

During the tense and tumultuous Vietnam War years, the ACLU-NC represented soldiers who were court-martialed for distributing anti-war leaflets and teachers whose credentials were threatened because they were arrested in political demonstrations.

As the lesbian and gay rights movement came out of the closet, the affiliate provided attorneys to protect gay organizations from police raids and to respond to general persecution by law enforcement.

An early advocate of reproductive freedom, the ACLU-NC defended three activists who were arrested for disseminating information about abortion techniques and helped eliminate criminal abortion laws in the state.

And as San Francisco’s counter-culture blossomed, the ACLU-NC was busy defending the First Amendment rights of street musicians, poets, and the world-renowned San Francisco Mime Troupe.

The political ferment of the 60s generated a significant growth in the affiliate’s membership, which reached 12,500 by the end of the decade.

In 1972, the ACLU-NC helped to author and pass a Privacy Amendment to the California Constitution. This innovative measure established the explicit right of privacy in the state, and became the legal underpinning of a wide and varied range of litigation: from protecting individual financial records and membership rolls of political parties to landmark victories guaranteeing the right to reproductive choice.

The organization also established the Police Practices Project to monitor, expose and challenge police abuse, from political spying on demonstrators to police round-ups of homeless people.

In support of the burgeoning women’s movement, the affiliate took cases focused on hiring, employment conditions, benefits, and residency requirements to ensure equal rights for women. The affiliate also hired its first woman Executive Director, Dorothy Ehrlich, who served in that position for 28 years.The organization fought for the rights of prisoners, laying the groundwork for religious freedom, decent medical care and safety, and the right to write and read inmate-edited newspapers. In psychiatric hospitals, the ACLU-NC successfully waged a major campaign against the forced drugging of patients.

The ACLU-NC participated in the lawsuit that ended the death penalty in California, a major victory that was to reverberate nationally and last a quarter century.

The end of the wars in Southeast Asia, new wars in Central America and the economic devastation in both continents brought many new immigrants to California. Many California and federal officials did not welcome the newcomers.

The ACLU-NC litigated against a probe, ordered by the U.S. Attorney, of bilingual ballot seekers and fought INS raids at workplaces and in immigrant neighborhoods. We published many of our materials—including popular pocket-sized “Rights on Arrest” cards—in English, Spanish, Chinese and several Southeast Asian languages.

In a major victory for freedom of expression, the affiliate helped secure the right to distribute leaflets and political literature at shopping centers, dubbed by the court the “modern-day town plaza.”

The affiliate founded the Lesbian and Gay Rights Project, which pursued lawsuits on behalf of gay men and lesbians who were denied benefits, refused jobs and security clearances, or fired. The Project authored and helped to implement the first domestic partnership ordinances in the country, laws that hundreds of other cities and states copied. The HIV/AIDS Project formulated public policy and model legislation that protected people with AIDS against draconian measures that would undermine public health.

The legalization of abortion by the U.S. Supreme Court gave rise to a rabid anti-choice movement that tried to chip away at the right to choose by eliminating options for young women, poor women, and women of color. The ACLU-NC sought to maintain Medi-Cal funding of abortions for indigent women after federal funding was cut off. In 1981, the ACLU-NC won a landmark victory in the California Supreme Court when Justice Matthew Tobriner, relying on the privacy amendment in the state constitution, wrote: “Once the state furnishes medical care to poor women in general, it cannot withdraw part of that care solely because a woman exercised her constitutional right to have an abortion.”

A subsequent case guaranteed that teenagers could receive an abortion without requiring parental or judicial consent—a key right for young women in abusive families.

We also fought the Reagan and Bush administrations’ war on the poor with cases defending the rights of families on welfare, SSI recipients and homeless people.

The beginning of the decade was marked by a massive effort to prevent the first execution in California in 25 years. The ACLU-NC Death Penalty Project directly represented Robert Harris. But our strenuous effort for clemency, a multi-faceted public education campaign, and appeals that went to the U.S. Supreme Court until the dawn of the execution, could not prevent the return of capital punishment to California. To carry on its work against state executions, the ACLU-NC was instrumental in bringing together legal, political and religious leaders to found Death Penalty Focus.

The Language Rights Project, an outgrowth of our immigrants’ rights work, created a groundbreaking docket of legal challenges to language and accent discrimination in employment, government services and the commercial realm.

Our efforts on behalf of the First Amendment were stretched to new limits with the growth of the Internet. Encompassing Silicon Valley and the heart of the hi-tech revolution, the affiliate made a special commitment to this new arena of expressive freedom, winning key cases supporting the rights of library patrons to have access to the Internet, and working alongside the national ACLU to protect privacy and prevent censorship in cyberspace.

Recognizing the need to encourage new generations of civil libertarians, the affiliate founded the Howard A. Friedman First Amendment Project for youth. The Project embarked on student-led conferences and exploratory field trips. The young people introduced the affiliate to many civil liberties violations in schools, leading to a fresh docket of students’ rights cases, including challenges to censorship of student murals, videos, and poetry; high school drug testing and searches; and support for lesbian and gay students facing violence and harassment.

We also witnessed an upsurge in right-wing ballot initiatives on race, immigration, criminal justice, and gay rights. Proposition 187, initiated by then-Governor Pete Wilson as a launch pad for a presidential bid, would have cut off education, health care and all government services to undocumented immigrants. We lost at the ballot box, but defeated the measure in court. Proposition 209 eliminated affirmative action in education, hiring and state contracting. We again lost at the ballot box, and—after an initial stunning win in the courtroom of Judge Thelton Henderson—in the Court of Appeals. Proposition 227 scrapped effective bilingual education programs. Voters passed measures to enact the Three Strikes law, to expand the death penalty and to incarcerate juveniles as adults. The initiative process—started by Governor Hiram Johnson to provide an independent democratic voice for the people when the Legislature was controlled by business interests — had turned into a nightmare.

As an antidote to Proposition 209, and in recognition of the growing resegregation of our educational and criminal justice systems, the ACLU-NC founded the Racial Justice Project. The Project, working with other civil rights groups, filed successful lawsuits challenging unequal admissions in the U.C. system and targeting deplorable learning conditions in schools that served communities of color.

The Project also launched the innovative “Driving While Black or Brown” campaign, a multi-faceted effort—including radio ads, billboards, a statewide hotline, town hall meetings, legislation and a lawsuit against the California Highway Patrol — to expose and stop the widespread practice of racial profiling by law enforcement. The campaign was replicated by the national ACLU and many other affiliates.

The government’s response to 9/11—round-ups and detention of thousands of Muslim, South Asian and Middle Eastern men; deportations without hearings; unblinking passage of the Patriot Act; special registration and racial profiling at airports—catapulted the ACLU, nationally and locally, into an unprecedented level of activity. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, we set up a special hotline for vulnerable communities, provided legal representation, and conducted “Know Your Rights” trainings. We later took on cases challenging government watch lists and surveillance, and we sued a San Jose-based company that aided the CIA in extraordinary rendition flights.

And now, as we face new challenges yet again, the ACLU of Northern California will continue to fight for the rights of all Californians.

Elaine Elinson is the former Public Information Director of the ACLU of Northern California. Stan Yogi is the former Director of Planned Giving of the ACLU of Northern California. They are coauthors of Wherever There’s a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers, and Poets Shaped Civil Liberties in California. Gigi Harney is the Creative Strategist at the ACLU of Northern California.