From Stravinsky to Ginsberg: The Triumph of Free Speech and Controversial Art that Challenges Us

Page Media

My parents are classical musicians. As a young girl, my parents demanded I practice my violin for hours, perfecting the work by the masters, gaining an understanding of the nuances that defined their artistic choices.

They told me that in order to be an innovator, one must study and know the history of the art form. There are only seven notes in an octave.

Throughout the history of classical music, only the visionaries pushed the boundaries by using these seven notes in ways that were new and uniquely theirs. In their own time, some of these artistic choices were considered controversial but later cherished as innovation.

Take for example Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring.” When first performed, in Paris in May of 1913, the modern nature of the music and choreography depicting a pagan fertility rite caused a near-riot in the audience, including booing, vegetables and punches being thrown in the audience.

At the time, the piece was considered to be too dissonant and emotionally unsettling but is now widely considered to be one of the most influential musical works of the 20th century. It was not performed for many years after its debut due to the controversy.

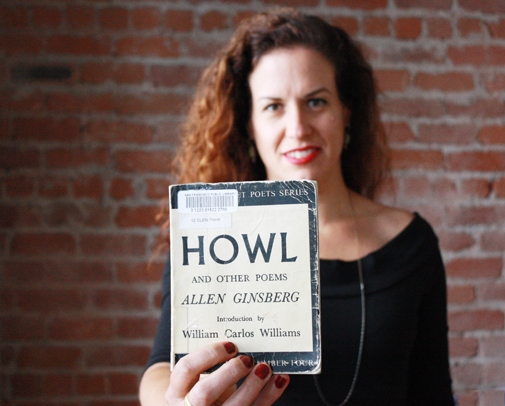

When I was about 19 years old I discovered both Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and the “Rite of Spring.” I was astounded that works of art such as these could pose a threat to the status quo enough to causing brawls or censorship.

Art causes us to feel and think, and indeed push to the boundaries of who we are and to consider the type of society we want to make possible.

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked…” begins Ginsberg’s “Howl.” The epic poem was read for the first time in San Francisco in 1955, where Ginsberg was living at the time.

“Howl” became a manifesto of the Beat Generation; weaving jazz rhythms and dissonance with post-World War II disillusionment and modern angst. Ginsberg’s lines were meant to be delivered in breath sized bursts like a bebop saxophone solo, filled with images of sexual freedom, intoxicants, and struggle in a maddening society filled with clashing values.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, owner of the City Lights bookstore in San Francisco, published “Howl and Other Poems” on Nov. 1, 1956.

Word spread about the controversial poetry, and the government took notice. In March, 1957 a San Francisco Collector of Customs seized more than 520 copies of “Howl and Other Poems” coming into the country for being considered obscene materials.

Ferlinghetti and City Lights Bookstore clerk Shigeyoshi Murao were charged with obscenity. The trial for People v. Ferlinghetti began in August, 1957, a bench trial in San Francisco Superior Court, making national news, and in turn, solidifying the voices of the Beat poets.

During the trial for Ginsberg’s “Howl”, much time was devoted to whether or not “Howl” had literary merit. The substance of a work of art was on trial in a court of law. Nine literary experts testified about the social value of “Howl.” Two of the prosecution’s witnesses refuted the poem’s literary merits, one of which claimed that “Howl” was merely an imitation of Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” (also a book banned briefly for obscene content).

The ACLU of Northern California formed a legal team, comprised of Al Bendich, J.W. Ehrlich and Lawrence Spieser, to defend Ferlinghetti -- and won the case. In a ruling issued on October 3, 1957, Judge Clayton Horn sided with the ACLU-NC.

In the unpublished opinion, Judge Horn wrote: “The freedoms of speech and press are inherent in a nation of free people. These freedoms must be protected if we are to remain free, both individually and as a nation… The theme of “Howl” presents ‘unorthodox and controversial ideas.’” He went on to state, “…[b]ut unless the book is entirely lacking in ‘social importance’ it cannot be held obscene.” … “The authors of the First Amendment knew that novel and unconventional ideas might disturb the complacent, but they chose to encourage a freedom which they believed essential if vigorous enlightenment was ever to triumph over slothful ignorance.”

Carey Lamprecht is a Litigation Assistant at the ACLU of Northern California.

Read more about the ACLU-NC’s defense of Howl publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti in the book “Wherever There’s a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers, and Poets Shaped Civil Liberties in California,” by Elaine Elinson and Stan Yogi.