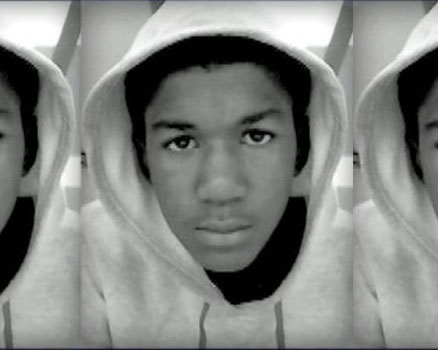

Trayvon Martin, George Zimmerman and Implicit Bias

Page Media

As the mother of an African-American boy, the tragic, unnecessary death of Trayvon Martin and the trial and subsequent acquittal of George Zimmerman have me heartbroken and filled with unanswerable questions. Does this verdict mean that some people view my son's (or my husband's or my father's) life as disposable? And how do parents like me protect our sons from people whose perceptions, unconscious or otherwise, will lead them to make incorrect assumptions based solely on skin color, while simultaneously ensuring that our children continue to be happy and hopeful instead of fearful and angry?

As I read and watch the coverage, I can't help but think that there is an important piece of the story missing from our national conversation – the concept of implicit bias. Implicit bias is a well-established social science theory; it occurs when someone holds explicit values against, say, racial prejudice, but is unconsciously influenced by negative views of, for example, another racial group. It does not mean that the person is hiding their own negative views; it means they actually don't know they have them.

Many social scientists at universities across the country have documented this phenomenon in a variety of arenas. In the criminal justice context, for example, studies have shown that people associate black physical features (such as dark skin and a wide nose) with criminality, and even that, in an MRI, when white people see, even subliminally, a black face, the "fear" part of their brain is more likely to light up than if they are shown a white face. My son is 4 years old, so even though he is not feared now, what happens when he is 11, 12 or 13?

What we are seeing in Trayvon Martin's death, George Zimmerman's trial, and our national conversation is this data playing out in real life and real time. Do the flip test: imagine the facts of this case, but with a black shooter and a white victim. What would the outcome in that case be?

Sadly, there are real-life examples to answer that question. Last fall Trevor Dooley, a 71-year-old black man who claimed to shoot his white neighbor in self-defense under the state of Florida's stand your ground law, was found guilty of manslaughter. Dooley, who believed race played a big part in his case, claimed that if the roles were reversed things would have looked drastically different.

In another Florida case, Marissa Alexander, a 32-year-old black mother of three and a domestic violence victim, was sentenced to 20 years in prison after a jury also rejected her claim to stand your ground. Alexander, who shot a warning shot into the air to scare off her abuser, is appealing her case.

In fact, in states with "Stand Your Ground" laws, 35.9 percent of white-on-black shootings are deemed justified when self-defense is invoked. By contrast, the same result is reached in only 3.4 percent of cases in which the reverse is true. Race unquestionably infused this process at every step of the way.

What can we do? Some of the social scientists studying implicit bias have conducted trainings for police departments and judges around the country to teach them about implicit bias, and to provide tools for officers and judges to help them counteract their own implicit biases. But more needs to be done. As a society, we must learn to talk about race in a new way, one that recognizes that racism doesn't only come with a white hood and a burning cross, but can instead seep into people's perceptions in a much more nuanced, but no less insidious, way. Only then will we really be able to begin to ensure everyone receives fair and equitable protection under the law. Our children deserve no less.

Read the official ACLU statement on the Zimmerman verdict »

Jory Steele is a former managing attorney with the ACLU of Northern California.