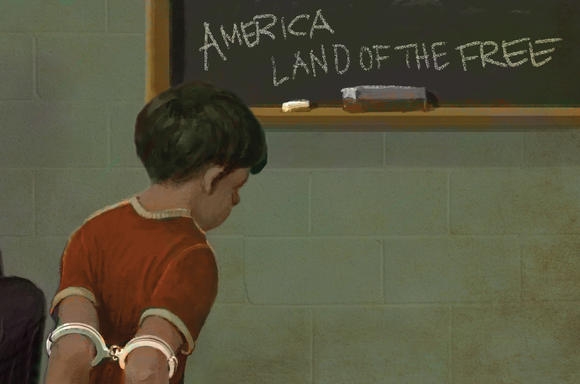

Since When Did Police Officers Replace the Principal’s Office?

Page Media

Back in the day, a student who broke school rules or otherwise misbehaved would be reprimanded by a teacher or sent to the principal’s office. But today, school administrators are increasingly relying on law enforcement to keep students in line, and the results can be dire.

Take the case of Michael Davis, a five-year-old student with disabilities in the Stockton Unified School District. A senior police officer in the school district’s police department decided to “scare him straight” after Michael acted out in his classroom, and the situation quickly spiraled out of control. When Michael got upset and could not calm down, the officer zip-tied Michael’s hands and feet and took him to a mental health facility. Michael’s family filed a lawsuit, and the police officer was finally dismissed from the department four years later, shortly after the family settled with the district for $125,000.

This incident, and many others like it, demonstrates how police officers are ineffective substitutes for counselors or other adults trained to work with young people who need guidance more than harsh discipline. Students who are treated as criminals for commonplace misbehavior are often traumatized and humiliated.

School administrators across California increasingly rely on police officers to enforce minor disciplinary infractions.

In a newly released report, “The Right to Remain a Student,” we examined 109 school-district policies on the use of law enforcement on campuses in California and found them often conflicting and vague, giving administrators wide latitude to request police assistance. Many schools have called the police to enforce minor violations like "disruption," "disturbing the peace," vandalism, tardiness, and inappropriate use of electronic devices — hardly criminal offenses.

In the San Bernardino Unified School District, for example, campus officers arrested around 30,000 students between 2005 and 2014, mostly for minor infractions like tagging and disobeying curfews.

We also found that these policies disproportionately target students of color and young people with disabilities, unnecessarily feeding them into the criminal justice system. Black students are three times as likely as white students to face school-related arrest. Students with disabilities are three times as likely as students without disabilities to be arrested on campus.

Rather than unjustly contributing to the school-to-prison pipeline, school administrators should call the police only if there is a real and immediate physical threat to student, staff, or public safety.

In 2013, the Pasadena School District developed guidelines that clarify the role of police on its campuses. Under these new rules, school staff cannot ask police officers to address incidents that involve school discipline. This progressive step has led to a significant decrease in school-based citations and arrests in Pasadena. Still, more needs to be done to ensure that district staff and police follow the rules, and that the district publicly and accurately report the data.

Similarly, school administrators should take back control of their campuses and stop relying on police officers to handle minor discipline issues, which only serves to criminalize students and push them out of school. Instead, school staff should address these issues themselves and correct student behavior with restorative justice and other more constructive practices.

Linnea Nelson is an Education Equity Staff Attorney with the ACLU of Northern California. Victor Leung is a Staff Attorney and the Deputy Director of Advocacy with the ACLU of Southern California.