After being enslaved and starved by two white cattle ranchers for more than two years, members of a Pomo Indian tribe rose up and killed their vicious captors. In retaliation, government troops from the U.S. Cavalry, working in concert with white vigilantes, slaughtered the Indian men, women and children who had taken refuge on an island north of Clear Lake in Clear Lake County.

As many as 200 Pomo were killed on the island and in the surrounding area. Many women and children were stabbed with bayonets. One of the few survivors was a 6-year-old girl named Ni’ka, later known as Lucy Moore, who hid in the bloodied waters and survived by breathing air through a reed. The seeds of this bloody conflict can be traced back to 1847 when two white settlers, Charles Stone and Andrew Kelsey, bought a cattle ranch where they kept several hundred local Pomo men as slave laborers. They were known for their brutal mistreatment of their workers, doling out starvation rations of four cups of wheat each day and refusing to allow the Pomo to fish on the land to feed themselves. The two men sexually abused Pomo women and children, including the wife of the local Pomo Chief Augustine. Those who resisted were whipped and lashed. One day, Stone gave 100 lashes to a young Pomo man. There are different versions of what led to the punishment. One report said he had been sent by his aunt to beg for more wheat. Another said that the young Pomo man had insulted Kelsey’s wife. What is not disputed is that after the lashing, one of the white settlers shot the youth in the head. After the murder, Pomo tribe members killed Stone and Kelsey. Bent on revenge, Kelsey’s brother rounded up a posse and began indiscriminately killing Indians. Many Pomo fled the ranch to an island, known as Bo-no-po-ti in the Pomo language, where Indians gathered every April for fish spawning season. Soldiers hunted them down. In the words of Captain Nathaniel Lyon, who led the attack, “the island became a perfect slaughtering pen,” as the Indians had no way of escaping soldiers and an onslaught of heavy artillery. “Bloody Island” also known as the “Clear Lake Massacre,” was one of many government-sanctioned slaughters of Native Americans under California’s official policy to exterminate Native Americans. Every May, the Robinson Rancheria Pomo Indians in Clear Lake County hold a sunrise ceremony and other events to remember those killed at Bloody Island.

In the words of Captain Nathaniel Lyon, who led the attack, “the island became a perfect slaughtering pen,” as the Indians had no way of escaping.

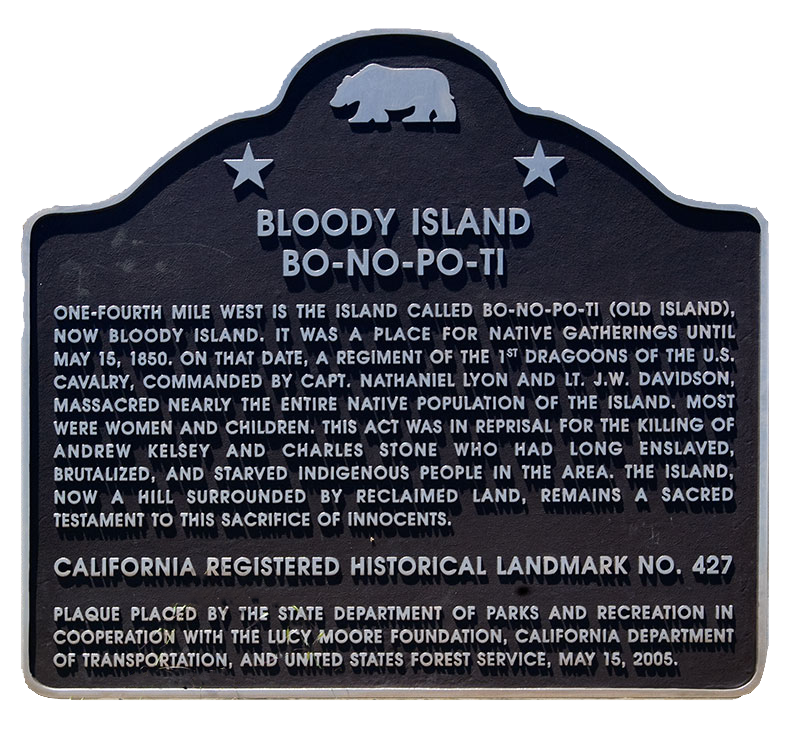

Historical plaque marking the massacre at Bloody Island in Lake County, California

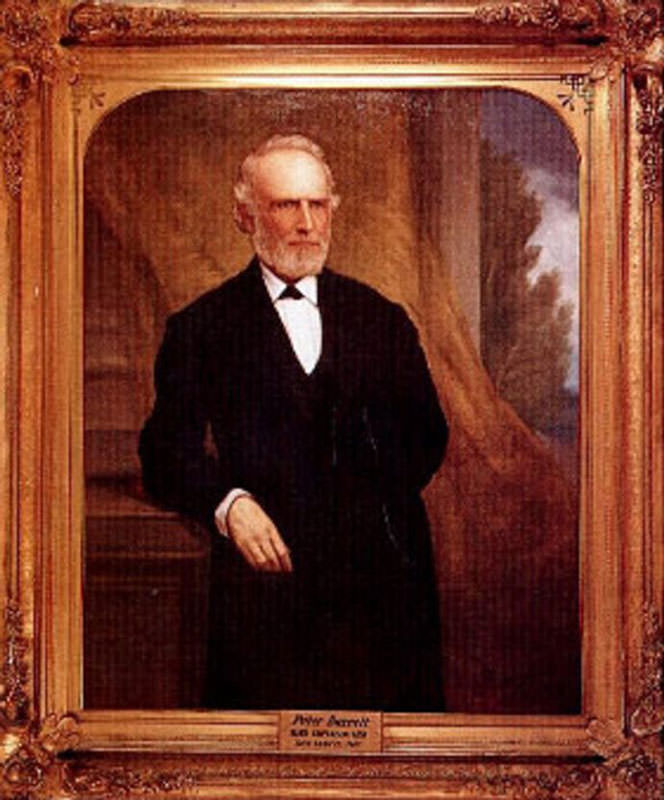

The first elected governor of California, Peter Hardeman Burnett, advocated for the genocide of Native people and tried to ban blacks from the state.

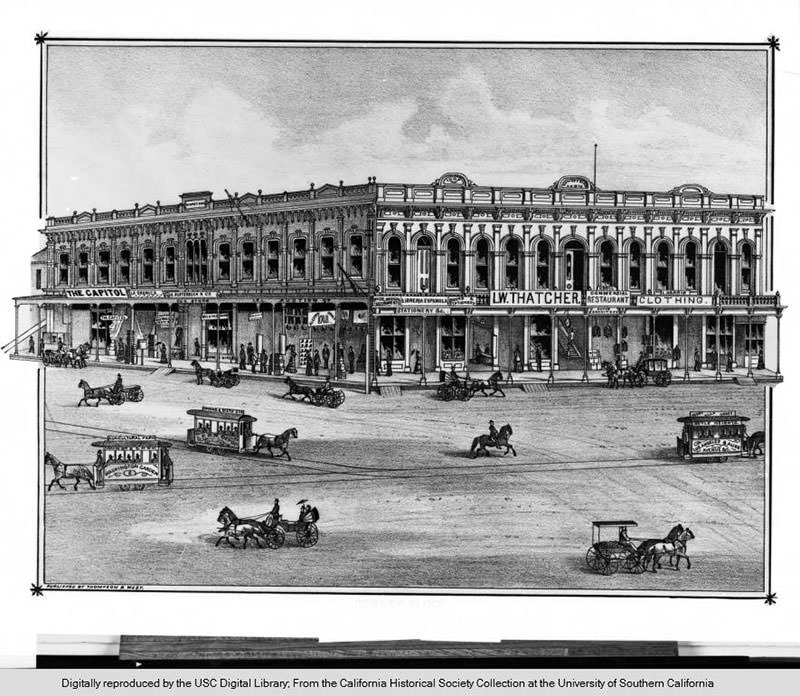

Today it’s the site of a federal courthouse in Los Angeles. But in the mid-19th century, a stretch of Main Street in downtown Los Angeles was a flourishing slave market.

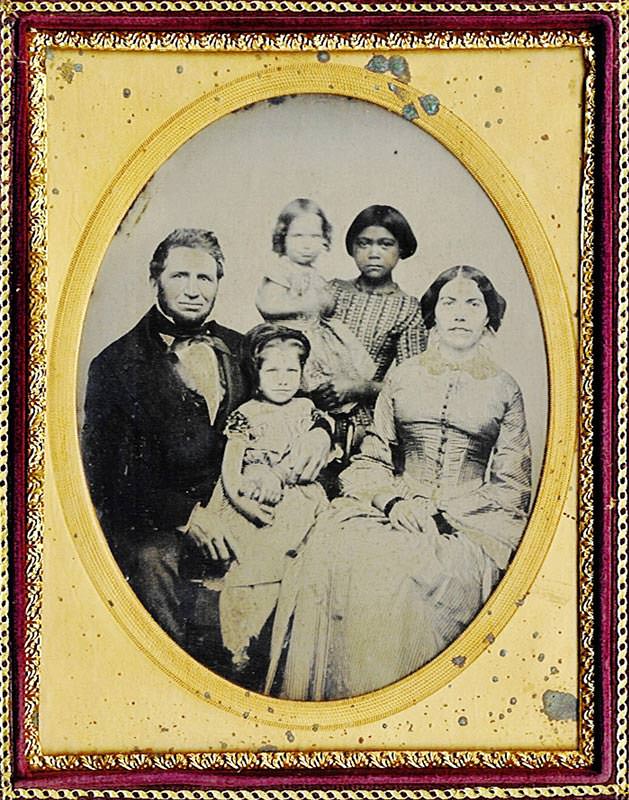

Looking to satisfy demands for cheap household labor, California passed a law that encouraged the kidnapping of Native Children.

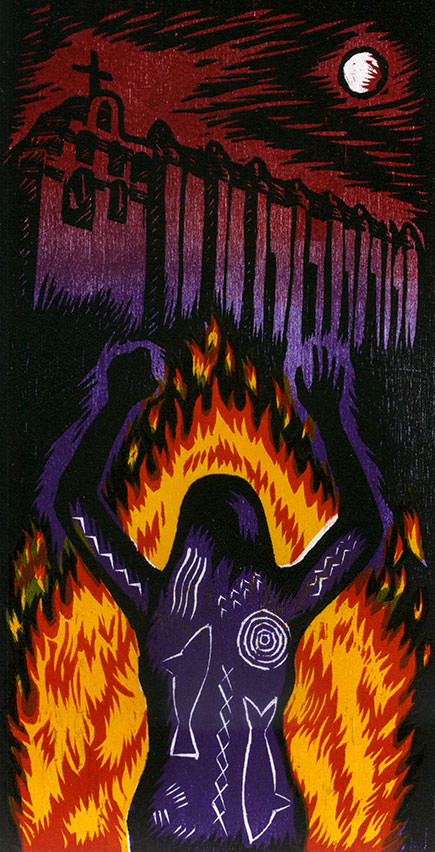

A medicine woman of the Tongva nation, Toypurina helped lead a rebellion against Spanish missionaries who invaded her homeland.

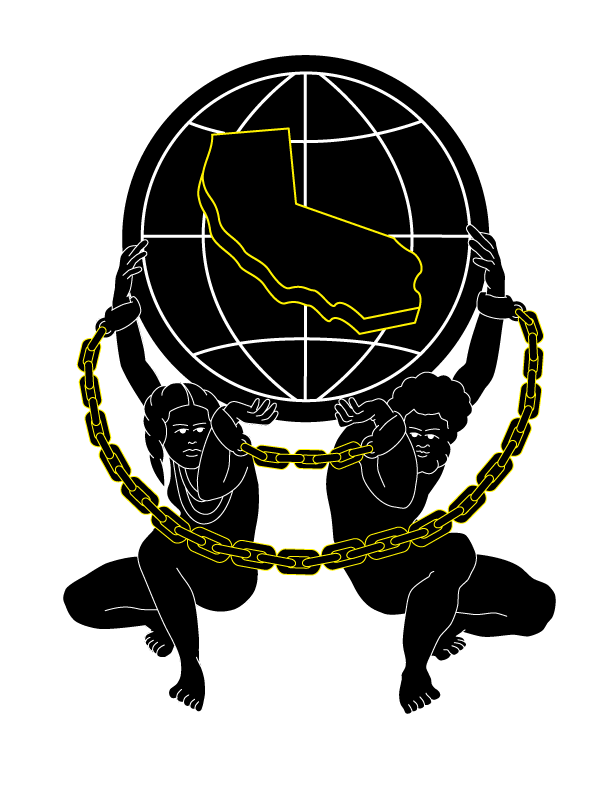

The mission of Gold Chains is to uncover the hidden history of slavery in California by lifting up the voices of courageous African American and Native American individuals who challenged their brutal treatment and demanded their civil rights, inspiring us with their ingenuity, resilience, and tenacity. We aim to expose the role of the courts, laws, and the tacit acceptance of white supremacy in sanctioning race-based violence and discrimination that continues into the present day. Through an unflinching examination of our collective past, we invite California to become truly aware and authentically enlightened.