In the first test of California’s Fugitive Slave Law, three formerly enslaved black men who had built a lucrative mining supply business were stripped of their freedom and deported back to Mississippi.

In 1849, Charles Perkins, a white Mississippian, set out for California to mine gold with an enslaved man named Carter Perkins. They were soon joined by two other male slaves from the Perkins plantation, Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones, who had been forced to migrate West, leaving their wives and children behind. The three men went to work for Charles Perkins mining gold.

Charles Perkins decided to return to the South and left his slaves in the care of a friend. He agreed to release them on the condition that they work for six months longer. Set free in November 1851, the industrious trio—Carter Perkins, Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones—launched a business transporting mining supplies in the gold fields near Ophir. They earned the equivalent of $100,000 in today’s dollars. But in 1852, California lawmakers passed a law that decreed that any black person who had entered California as a slave before statehood was the legal property of the slaveholder who brought them. Shortly after the law’s passage, Charles Perkins filed a legal action in California, demanding the return of his human “property.” He wrote to a cousin who contacted the Placer County Sheriff, whose men seized Carter Perkins, Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones from their cabin in a midnight raid. A justice of the peace ordered the men deported to Mississippi. The black community mobilized, raising funds to fight for the men’s release. They hired Cornelius Cole, a prominent anti-slavery attorney, who argued before the state Supreme Court that since California’s Constitution banned slavery, the Fugitive Slave Law was unconstitutional. However, pro-slavery justices dominated the court and ordered the men deported. They were quickly forced onto a steamboat with Charles Perkins’s representatives. One unconfirmed news report claimed they escaped from their captors while the ship was docked in Panama, but their fate is unknown.

California Book of Statutes, 1852, Chapter 33: Respecting Fugitives from Labor, and Slaves brought to this State prior to her admission into the Union: “When a person held to labor in any State or Territory of the United States under the laws thereof, shall escape into this state, the person to whom such labor or service may be due, his agent or attorney, is hereby empowered to seize or arrest such fugitive from labor, or shall have the right to obtain a warrant of arrest for such fugitive... Court Ruling: The State of California has certainly not entered into any contract with free negroes, fugitives, or slaves, by providing in the constitution that neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist in this State, which would prevent her, upon proper occasion, from removing all or any one of these classes from her borders.

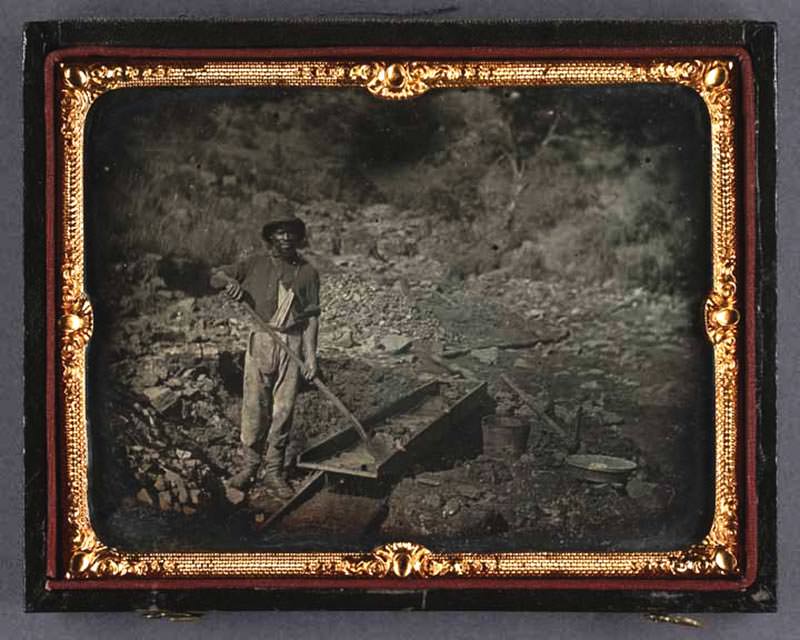

Photo: Black miner during Gold Rush era

Credit: Courtesy of the California History Room,

California State Library, Sacramento, California

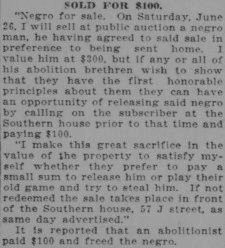

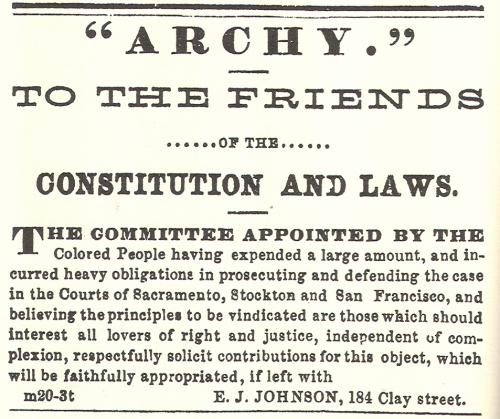

Photo: Advertisement for black slave, originally published in San Francisco Herald / Credit: Sacramento Union, Volume 211, Number 44, 14 December 1919, Courtesy of the California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside

Three formerly enslaved Black men were living their California Gold Rush dream, building a lucrative mining supply business in just a couple of months. But one cool spring night in 1852, an armed posse of white men burst into their cabin and arrested them, claiming that they were fugitive slaves. In our pilot episode, we explore a little-known California law that unleashed racial terror on Black people and made a mockery of the state constitution's ban on slavery.

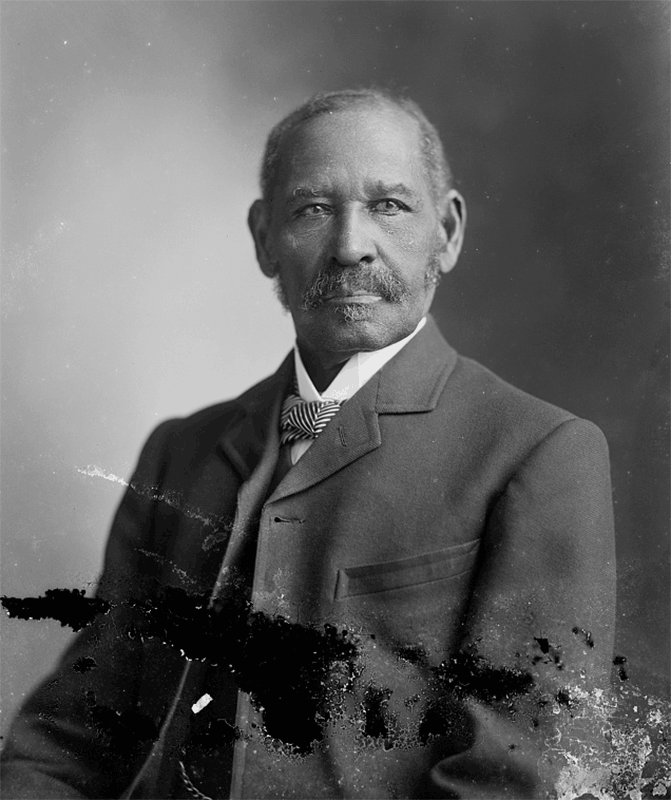

After waging a long battle against California’s anti-black laws, Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, a prominent civil rights activist and entrepreneur in San Francisco, helped lead a migration of several hundred African Americans to Victoria, British Columbia.

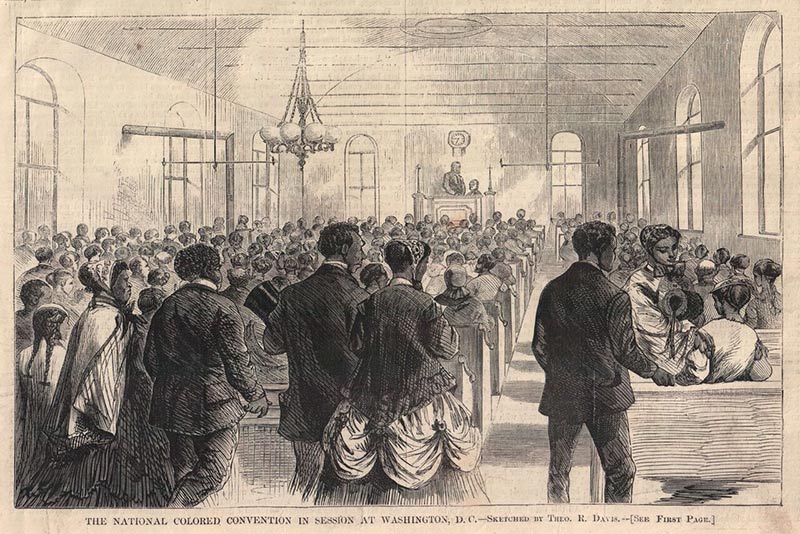

The Colored Conventions were a monumental organizing effort by black people across the country to fight for full citizenship rights. The conventions laid a foundation that the civil rights movement would build on.

In one of the most celebrated fugitive slave cases in California, Archy Lee, a young black man who had been brought to the state from Mississippi, escaped and waged a successful legal battle for his freedom that went all the way to the federal courts.

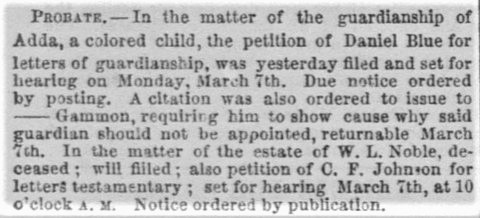

Daniel Blue, a black laundry man from Sacramento, went to court to free an enslaved young African American girl in what’s believed to be California’s final slave case.

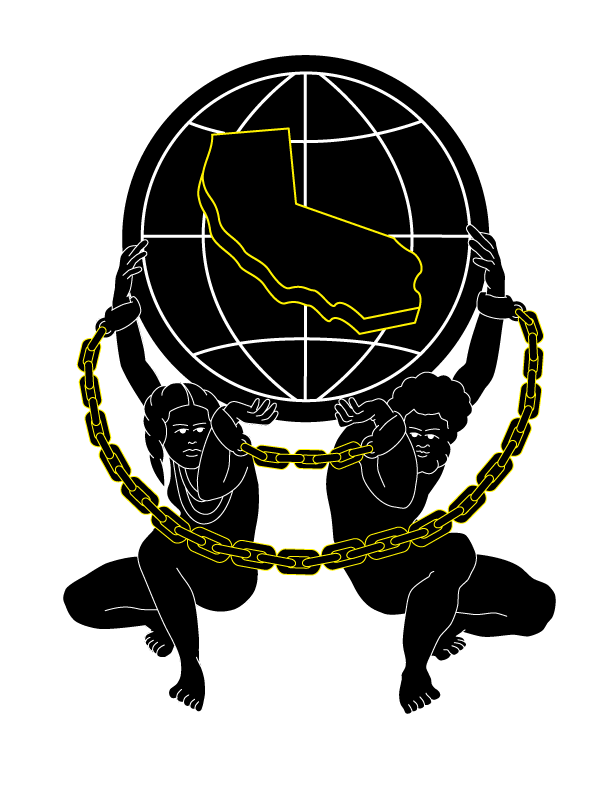

The mission of Gold Chains is to uncover the hidden history of slavery in California by lifting up the voices of courageous African American and Native American individuals who challenged their brutal treatment and demanded their civil rights, inspiring us with their ingenuity, resilience, and tenacity. We aim to expose the role of the courts, laws, and the tacit acceptance of white supremacy in sanctioning race-based violence and discrimination that continues into the present day. Through an unflinching examination of our collective past, we invite California to become truly aware and authentically enlightened.