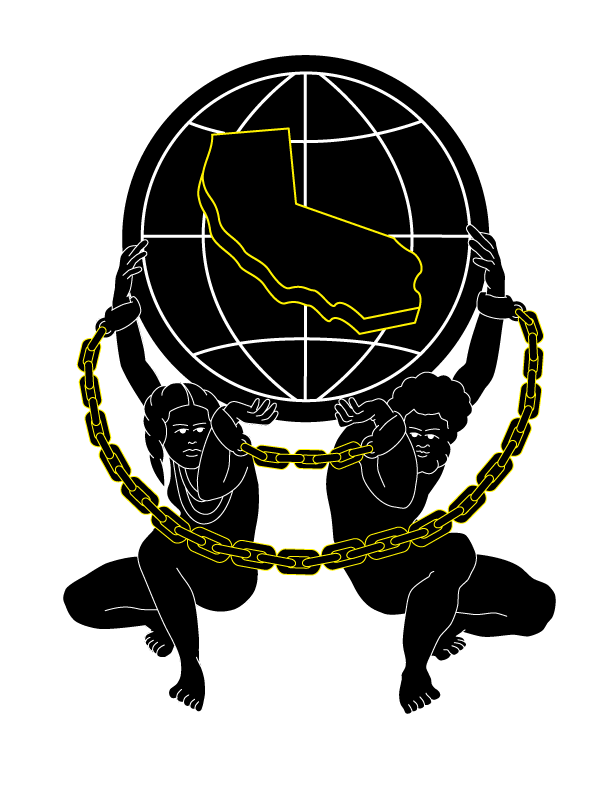

Artwork courtesy of the Tom Feelings Collection, LLC

August 12, 2021 | Pilot Episode: The California Fugitive Slave Law

[music]

Tammerlin Drummond: It's a cool spring night in 1852. Carter Perkins, Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones, three formerly enslaved black men are asleep in a cabin. All of a sudden, the front door busts open. It's the county sheriff and he's with a posse of white men. They roust the startled men from their beds at gunpoint. They tie them up, steal $2,000 worth of gold dust, cash and other property from them. That's about $65,000 today. Then, they throw the men into their own wagon and use their own team of mules to whisk them away in the dead of night.

Stacey Smith: The goal here was to make sure that none of the men's friends or neighbors knew what was going on, they would just be gone in the morning.

Tammerlin: Just imagine, the men have no idea where they're being taken, and after a terrifying ride, they find themselves in front of a justice of the peace. He declares them fugitive slaves and orders them sent back to a slave holder on a Mississippi plantation, who had filed a legal claim saying that they were his property. Now this might sound like some nightmare story out of the pre-Civil War, but it's not. It happened right here in the supposedly free state of California.

I'm Tammerlin Drummond. From the ACLU of Northern California, this is Gold Chains. It's our new podcast about the hidden history of slavery in California, where we unearth stories from a dark chapter of California history that you almost certainly didn't learn about in school. Welcome to our pilot episode about the California Fugitive Slave Law of 1852. It was one of many racist schemes concocted by white southern transplants who were determined to gain a foothold for slavery, even though California was a free state. Instead of enforcing the Constitution's ban on slavery, government officials at every level used their power to make it harder for enslaved Black people to escape and free themselves.

Stacey Smith is an associate professor of history at Oregon State University. She has spent decades researching California’s slavery past and wrote a book about it.

Stacey: What we really need to think about here is the rule of California in perpetuating and benefiting from enslavement. California is such an outlier, it's one of the only free states that is so friendly to the interests of pro-slavery southerners. State officials didn't have to do that. The Constitution was a free Constitution that banned slavery.

Tammerlin: Yet somehow, California managed to develop a reputation as a progressive land of opportunity. Most school children are taught that this was a free state and never had slavery. The discrimination and racial violence that was rampant in other parts of the country just didn't exist here. During the gold rush black people had just as much opportunity as anyone else to make a ton of fast money digging for gold or providing the many other services the gold miners needed. But Stacey Smith has a different take on this version of the California dream.

Stacey: I'm actually trying to complicate that and say, "no," actually, if we look at California and in some respects really places in the broader west during this period, we actually see that many of the same conflicts, especially over slavery and race, are happening in California at the same time as in the rest of the nation. Enslaved people didn't come to California willingly. The California dream was not for them, it was for the white southerners who claimed ownership of them, and so that really goes counter to the stories that we tell ourselves about not only what the gold rush was and what it was supposed to be, but also really what California is and what it's supposed to be.

Tammerlin: In 1619 the first enslaved Africans arrived in Jamestown, Virginia. The date has come to symbolize the official start of slavery in the British colonies. 2019 was the 400th anniversary. That led to a lot of conversations about how slavery gave birth to the racist laws, policies and customs that to this day affect almost every aspect of American society, but how come almost no one was talking about California?

Stacey: We actually have the documentation that slavery happened here in California. It's just that no one has really dug into this material and presented it to the public in a way that would educate Californians about this really horrible part of its history. Because there hasn't been a lot of scholarship that reaches out to people that really challenges that narrative of a free California, they can feel free to make statements like, "slavery never really happened here," or "isn't it nice that we've escaped to a place that doesn't have all of that baggage?"

Tammerlin: At the ACLU of Northern California, we decided to do some digging of our own to highlight the history that Stacey Smith says has been hiding in plain sight. This podcast is a spin-off of our earlier public education project that we launched in 2019.

Candice Francis: Looking at slavery in California made perfect sense to us because so much of the work that we do revolves around the inequities and the disparities that come from a system of slavery that was practiced in California.

Tammerlin: That's Candice Francis. She heads the ACLU communications department that produced the Gold Chains project. She says that California's involvement with slavery was deliberately hidden.

Candice: Somewhere along the line, and again, this is not just California, it's across the United States, this is not a pretty story to tell. People who are trying to build the state are not going to bring out the skeletons and tell the story of their own inhumanity to man. The history has been erased from the schoolbooks. People who live in California, who were raised and educated here, do not learn this history. That's why it's really important that in this time, especially now when there's a racial reckoning happening throughout the country, and when we see cries for the reversal of so many ills, then it is important to understand the genesis of all of that. You can't move forward without knowing what the past wrought.

Tammerlin: Last year, the state of California finally took a first step to acknowledge the state's complicity in the enslavement of Black people. The legislature passed a bill that created a task force to make recommendations for reparations for African Americans. It's the first state in the country to do so. California Secretary of State Shirley Weber wrote the historic bill known as AB 3121 while she was still an assembly woman. Here she is speaking at the task force's first meeting in June.

Shirley Weber: We are here today because the racism of slavery, birth and an unjust system, and a legacy of racial harm and inequality that continues today in every aspect of our life. We cannot separate the things that people are crying for in the streets in terms of justice from what has happened in the past, and that we are here, you're here today, not just to seek an answer to say was there harm, but your task is to determine the depth of the harm and the ways in which we are to repair that harm.

Tammerlin: If this is the first time you're hearing that California had slavery, you probably wonder, how was this possible in a free state? Stacey Smith breaks it down for us.

Stacey: California is really a pretty wide open place after the United States takes it from Mexico in the 1840s. What really happens is that hundreds of thousands of people, they rushed into California for the gold discoveries. There's no organized territorial government. Law enforcement and judicial structures, they're not non-existent, but they aren't especially strong. They're just thrown together in this last-minute affair. I'd say that there's a gap of almost two years, maybe about a year and a half, where there isn't a constitution in force. California isn't a state, it's not even a territory. That gives enough time because it's really that same period, the height of the gold rush migration. It gives enough time and enough motivation for slave-holding white Southerners to move in with enslaved people, and they go into the mines, they spread out, and they begin to work, digging gold.

Tammerlin: Charles Perkins was one of them. He was the young son of a wealthy Mississippi plantation owner, and in the summer of 1849, decided to join the mass migration of gold rushers going west. He took an enslaved man from his father's plantation with him. We really don't know much about Carter Perkins. He was about 21 years old, and most likely had worked in the fields picking cotton. The two men probably had the same last name because enslaved people often took or were given the surnames of the plantation owner. Once in California, Charles Perkins headed for El Dorado County and put Carter Perkins to work digging for gold. It was exhausting work and some miners died from diseases like scarlet fever and cholera. After a short time, some of Charles Perkins' friends brought two more enslaved men from the Perkins plantation to California to mine gold. The new arrivals, Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones were older, middle-aged men with families. Robert Perkins had a wife and five children that he'd had to leave behind. After about a year and a half, Charles Perkins decided to go back home to Mississippi. For some reason, though, he decided to leave the three enslaved men behind, perhaps because he couldn't afford to pay their way back. He hired them out to a neighbor named Dr. Hill. The two white men made them an informal deal.

If they worked for Dr. Hill for six more months, he would set them free. Charles Perkins tells Dr. Hill:

Stacey: "You watch over these enslaved men. Once they've performed a certain amount of labor for you, go ahead and set them free." Or at least that's how Dr. Hill, who was this friend of Charles Perkins, interpreted what he was supposed to do.

Tammerlin: Six months later, Dr. Hill set the men free, but as Stacey Smith explains, there's a problem.

Stacey: It's not clear that they got any freedom papers. Freedom papers are basically these legal documents that you draw up before a judge and that says on the paper that, "here's my proof that I'm free." Then, you probably get a white witness or two, who testifies, "yes, I know that this is a free person." As far as we know, the enslaved men, in this case, probably didn't get those papers drawn up, or if they did, the papers were lost or stolen. I think it's a pretty good assumption that if they did have these freedom papers, the men who raided their cabin in the middle of the night probably took them and kept them out of the process later on.

Tammerlin: What must it have been like for three grown men who had been enslaved their whole lives to finally taste freedom? Carter Perkins was still a young man, but Robert Perkins was 42, and Sandy Jones was 57. They had spent many years in bondage. But for the first time, they are their own masters. According to Stacey Smith, they don't waste any time.

Stacey: They eventually buy a team of mules and a wagon, and they become quite successful. They're hauling goods back and forth among all of these gold mining towns. All of the men, except for Carter Perkins, who was the youngest, were family men. They were middle-aged men who, as far as we know, had children and families back on the Perkins plantation in Mississippi. There's been a lot of speculation that they were trying to earn enough money as quickly as they could to buy their family members and bring them back out to California, or at least to be able to go back to the East Coast and perhaps buy the freedom of their family members and settle elsewhere.

Tammerlin: Little did they know that pro-slavery Democrats and the California Legislature were planning to unleash racial terror on Black people in the state. California entered the union as a free state under the compromise of 1850. The new constitution had a clause, "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crimes, shall ever be tolerated in this state." What did this mean for enslaved black people who had been brought to California before statehood? Were they now automatically free?

Taylor Bythewood-Porter: Enslaved people who were brought into the state in 1848 or 1849, by the time statehood arrived in 1850, they would find themselves in the California Hills. It was very remote. They were able to run away in the Hills and find sanctuary with other free African Americans or with abolitionists and allies. This definitely caused a problem for those enslavers.

Tammerlin: That's Taylor Bythewood-Porter with the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. She was one of the curators for the exhibit California Bound: Slavery on the New Frontier, 1848–1865. It was staged on the 400th anniversary of 1619. It was a rare examination of African American enslavement in the state. Bythewood-Porter says that as more and more formerly enslaved black people started running away, slaveholders became increasingly agitated.

There was a federal fugitive slave law that required government authorities and private citizens to help slave owners recapture formerly enslaved people who had fled to free states, but that didn't help California slaveholders. That's because Black people who escaped in California didn't cross any state lines. Their enslavers had voluntarily brought them here.

Taylor: When enslaved people started to bring their court cases to try to fight for their freedom, the law definitely favored those who were enslaved at that moment in time, especially if they didn't cross any state lines. In the eyes of the law, they were free, and so this really aggravated a lot of the southern Democrats and politicians.

Tammerlin: Now, at this time, about a third of the white people living in California were from southern slave-holding states, and a surprising number of them got elected to public office. They were mayors, local sheriffs and judges, state lawmakers, and US senators. They had a lock on the State Supreme Court. Southern slaveholders and their allies wielded the full force of their political power to fight for a foothold for slavery. On April 15th, 1852, the California legislature passed its own fugitive slave law. It gave slaveholders one year to collect their enslaved persons and take them back to their home state. Charles Perkins got wind of the new law.

He probably also found out from some of his family members still in Gold Country that Carter Perkins, Robert Perkins, and Sandy Jones had done quite well for themselves. Taylor Bythewood-Porter says this is what happened next.

Taylor: Their former enslaver, who is now in Mississippi, he ended up writing a letter to his cousin who was still in California in the area at the time, and he told him to come and pick up his people.

Tammerlin: That cousin was part of the posse that broke into the men's cabin, which is where we began our story. News of the arrests quickly made its way to Sacramento's free Black community. It was small but mighty. Black churches, businesses, and civic organizations all joined forces with their white abolitionist allies to raise funds to defend the men. They hired a young anti-slavery attorney named Cornelius Cole, who argued that the California Fugitive Slave Act violated the state constitution’s ban on slavery. Cole got death threats for representing the formerly enslaved black man.

Taylor: It definitely took a lot of courage for white lawyers to defend formerly enslaved people. To be hired by a group of African-American people to defend another African-American, that lawyer needed to be brave and have courage. That's what these men were, to be able to stand up and say “no,” and to fight for the rights and equality of African Americans.

Tammerlin: Some of the lawyers Cole got in touch with to help with the defense clearly didn't have the purest motives. One wrote a letter speculating that they could probably extract $5,000 from the black community to pay for the men's legal fees, which is about $170,000 today. The Perkins case went all the way to the California Supreme Court, where it was heard by two pro-slavery judges. They said slaveholders had a right to bring their property into the state and that the California constitution could not deprive them of that right.

They then ordered the men immediately handed over to Charles Perkins’ representative. Here's what California's highest court had to say in its ruling. Here's Marshal Arnwine from our ACLU Criminal Justice team, reading an excerpt from the Perkins ruling.

Marshal Arnwine: Slaves are not parties to the Constitution, and although persons, they are property and without immunities. There is no provision there for emancipation.

Tammerlin: Furthermore, that anti-slavery clause in the Constitution? It was merely quote, “a declaration of principle.” It wasn't a real law, at least when it came to the rights of Black people, enslaved or free. On a windy fall day, Carter Perkins, Robert Perkins, and Sandy Jones were forced to board a steamer at San Francisco Harbor bound for Panama enroute to Mississippi. There's no official record of what happened to them after that. One newspaper claimed the man had escaped when their ship docked in Panama. Did they somehow manage to free themselves? Could they have possibly returned to Mississippi after the Civil War to rejoin their families?

One thing we do know is that the Perkins ruling had a chilling effect on the Black community. There were about 2,000 Black people living in the state in the early 1850s, and most of them had arrived during the gold rush. Any Black person could be arrested under the state's fugitive slave law. All it took was for a white person to say that someone Black was their escaped slave, and there was no proof required. Here's Taylor Bythewood-Porter again.

Taylor: There was always that fear of a mob coming to take you away in the middle of the night. Enslaved and free African Americans that arrived in California, even after statehood, could easily fall victim to fraud and kidnapping, and be forced to go back into enslavement.

Tammerlin: The law was supposed to expire after one year, but it kept getting renewed. It didn't finally end until 1855, which meant that if you were an enslaved Black person who came to California during the gold rush, you could very well have spent six years enslaved in a supposedly free state. There are newspaper reports of dozens of Black people who were forcibly returned to slave states under California's Fugitive Slave Law. Who knows how many cases weren't reported that went under the radar? According to Taylor Bythewood-Porter, this racial assault on African Americans gave rise to one of the first black activist movements in California.

Taylor: You're really starting to see the development of more organizations, churches, individual people coming together. At this time you're also really starting to think of California being its own kind of underground railroad, people assisting and helping one another.

Tammerlin: The Perkins ruling is one of the most important court decisions in early California history. You basically have the state Supreme Court green-lighting slavery in a supposed free state. Why isn't any of this being taught in California public schools? Here's Taylor Blythewood-Porter again.

Taylor: I think the main reason why this particular information isn't really covered in textbooks is, for me, I really like to think about who's writing these history books? Who are the publishers? It's so much easier to just sweep it under the rug, just to stick with the one narrative that California entered into the Union as a free state, which it was, and it did, but they're omitting all the other information that followed. You would really need to be a scholar or really dig into this information to really find it. You actually have to know what you're actually looking for. Just do a Google search on California slavery law, 1852. You really have to type it in verbatim.

Tammerlin: Even after the California fugitive slave law was finally off the books, slavery continued in the state, at least until 1864. That was just one year before the end of the Civil War.

Taylor: It wasn't necessarily picking cotton and farming agriculture, like it was in the South. It was a lot of mining, domestic work, and selling people out for labor. Women and children, especially during this time period, they suffered the most, because once they were behind the closed doors of their enslavers, nobody really knew what was going on. They were just small little footnotes in a newspaper article. It would say something like "negro girl" and something else happened. Who is this girl? She has a name. She has a story. What happened to her? These people have stories. They have feelings, and it's like, they just disappeared.

It's really important to be able to talk about these people because that's what they were, people.

Tammerlin: Gold Chains is produced by the ACLU of Northern California with technical production by Dax Brooks and music by Dax Brooks. The episode was written by me, Tammerlin Drummond. A special thanks to our guest historians, Stacey L. Smith and Taylor Bythewood-Porter, for sharing their wealth of knowledge with us on this episode. Stacey Smith's book is Freedom’s Frontier: California and the Struggle over Unfree Labor, Emancipation and Reconstruction. You can visit the California-bound slavery exhibit virtually that Taylor Bythewood-Porter co-curated at caamuseum.org.

Thanks to Candice Francis, our ACLU communications director, and the rest of our amazing Gold Chains team, Brady Hirsch, Carmen King, Gigi Harney, and Steven Wilson. Thank you also to Abdi Soltani, our executive director, for his continued support of the Gold Chains project. We also want to thank Marshal Arnwine, Eliza Wee of Dogmo Studios, and Eric J. Molinsky. Finally, we'd like to thank our partners on the Gold Chains public education project. KQED, the California Historical Society, the Equal Justice Society, and Laura Atkins co-author of Biddy Mason Speaks Up.

Our website is goldchainsca.org.

Thank you so much for listening to our Gold Chains pilot episode. If you appreciated what you heard, please subscribe wherever you listen to your podcasts. It would really mean a lot to us if you'd like us or rate the show.

I'm your host Tammerlin Drummond.

[00:24:59] [END OF AUDIO]

The mission of Gold Chains is to uncover the hidden history of slavery in California by lifting up the voices of courageous African American and Native American individuals who challenged their brutal treatment and demanded their civil rights, inspiring us with their ingenuity, resilience, and tenacity. We aim to expose the role of the courts, laws, and the tacit acceptance of white supremacy in sanctioning race-based violence and discrimination that continues into the present day. Through an unflinching examination of our collective past, we invite California to become truly aware and authentically enlightened.