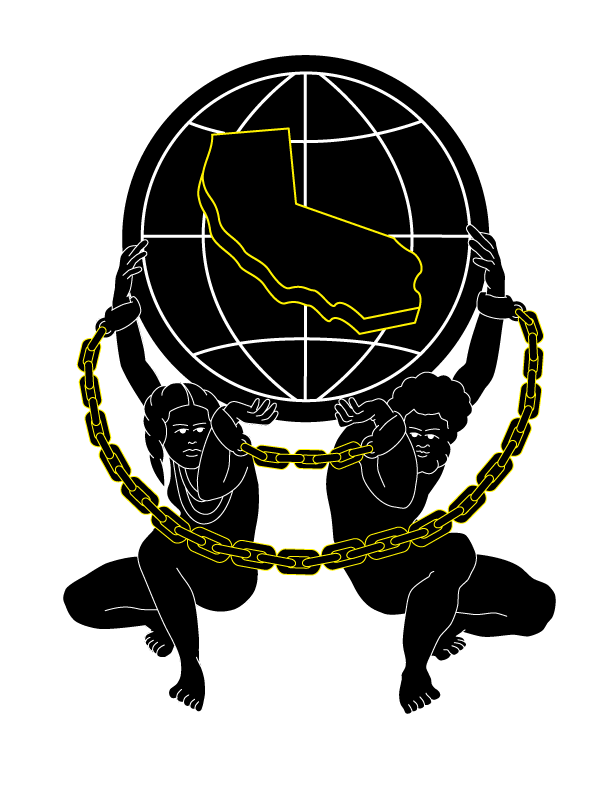

Artwork courtesy of the Tom Feelings Collection, LLC

February 24, 2022 | Episode 2: Black Testimony Matters

George Gordon: [00:00:18] My name is George W. Gordon. I moved out west from Troy, New York, because I heard there were better opportunities for colored people in California. I've got my own barbershop in San Francisco and I'm married with a son.

Tammerlin Drummond: [00:00:35] George Gordon is well liked and respected in Gold Rush-era San Francisco, but because he's Black, the law doesn't offer him the same respect.

Voice Actor: [00:00:49] No Black or mulatto person or Indian shall be permitted to give evidence in favor of or against any white person in a criminal case. Every person who shall have one-eighth part or more of Negro blood shall be deemed a mulatto, and every person who shall have one half of Indian blood shall be deemed Indian. An act concerning crimes and punishment. April sixth, 1850.

Tammerlin: [00:01:30] That's the same year California joined the union as a supposed free state. It's also when its founders started to strip away the citizenship rights of people of color, including African-Americans. I'm Tammerlin Drummond. From the ACLU of Northern California, This is Gold Chains. It's our podcast about the hidden history of slavery in California. We're telling you stories from a chapter of state history that you almost certainly didn't learn about in school. At the dawn of statehood, the laws don't allow George Gordon to protect himself or his property. His statements under oath aren't valid in a court of law. He can't vote or send his son to public schools because racist laws won't let him.

Dana Weiner: [00:02:23] And while they're put in place in a piecemeal fashion, it's not as if they, you know, jump up and say, Hey, here are all these laws we're placing to restrict the rights of Black people

Tammerlin: [00:02:31] At Wilfrid Laurier University. Dana Weiner studies how Black Californians pushed back against these limits.

Dana: [00:02:40] Nonetheless, these laws enable governments to collectively discriminate against African-Americans through their state laws and often in their constitutions.

Tammerlin: [00:02:51] She says California and other states enacted so-called Black laws to establish the West as a place where only white people could claim and settle the land.

Dana: [00:03:01] The Legislature even tried to block African-American migration to California five times between 1849 and 1858.

Tammerlin: [00:03:10] George Gordon and other Black Californians started organizing to defeat these efforts. A few years before California built its state capital, another event in Sacramento asserted the citizenship of everyone in the new state. The first California Colored Convention met in the sanctuary of the oldest African-American church on the Pacific coast. Bethel African Methodist Episcopal, now known as St Andrews AME. The men who gathered for the earliest recorded Black civil rights activism in California were businessmen, ministers, entrepreneurs and gold miners. Longtime historian Clarence Caesar says it wasn't easy for them to travel

Clarence Caesar: [00:04:01] In order for, say, a person from the Bay Area to get to Sacramento. They would have had to go by basically by steam transport, making the trip from San Francisco to Oakland first and then finding a way to get down the Sacramento River through the Cartagena Straits.

Tammerlin: [00:04:17] This is probably how George Gordon made his way to the three day colored convention in December 1856. The convention president calls the meeting to order.

Convention President: [00:04:32] Gentlemen, the occasion, which has brought us together is one of great importance. The object we seek equal testimony in the courts of this state is deserving of our most earnest effort.

Tammerlin: [00:04:47] Packed into the sanctuary are 61 Black men. Most wear formal attire. They are the elected delegates from the Black population centers in California. Some are freeborn, others formerly enslaved.

Convention President: [00:05:03] No, we are not without many enemies who would rejoice to see confusion and division in our midst, but let us enter upon our deliberations in a spirit of kindness and conciliation if there ever was a people among whom union was necessary. Union of purpose, of spirit and Action for the sake of success, then is it necessary to us.

Tammerlin: [00:05:38] As they get down to business, disagreements arise about how quickly to pursue their goals. Barbershop owner George Gordon, representing San Francisco, is in the thick of it.

Dana: [00:05:50] Gordon not only attended the 1856 California Black Convention, but he actually took a pretty active role in the proceedings.

Tammerlin Drummond: [00:05:58] Historian Dana Weiner again.

Dana: [00:06:01] He gets into a debate with a more radical activist named William Newby,

Tammerlin Drummond: [00:06:07] Who wants a more forceful approach toward abolishing the testimony laws. Here's some of what the convention minutes recorded from his and Gordon's exchange.

William Newby: [00:06:20] We have permitted this sort of policy long enough. Not that we should make it a point to offend, but speak frankly and truthfully.

Tammerlin: [00:06:29] Gordon prefers requests to demands

George Gordon: [00:06:33] It becomes us to be cautious in view of the circumstances of our position. We are soliciting the attention of the people to the injustice of the laws, which deprive us of testimony and our children of public schooling.

Tammerlin: [00:06:50] Newby wants to skip the niceties.

William: [00:06:53] Intelligent whites know and appreciate intelligence wherever they see it. They despise cowardice and duplicity. We know that we should act and they know they would in the same circumstances because it is right. So to act.

Tammerlin: [00:07:09] Not so fast, Gordon says.

George Gordon : [00:07:12] When we shall go to the State House asking for the repeal of those laws, we shall petition respectfully.

Tammerlin: [00:07:21] Men may have been the only ones present, but without women there would have been no colored conventions.

Rosa Pleasant: [00:07:29] There was overwhelmingly women hairdressers who were funding these meetings of of men to change the laws.

Tammerlin: [00:07:38] Rosa Pleasant is an activist and a middle school teacher. When she was an undergrad at Occidental College in Los Angeles, she worked on a project documenting the little known but significant history of the nationwide Colored Convention Movement.

Rosa: [00:07:54] It's a story of triumph. It's a story of organizing. It's a story of community. You have states being created and formed, and in their infancy you have Black communities, Black, free communities that are reimagining society. And what's a just society.

Tammerlin: [00:08:17] At the conventions, they agreed to collect signatures on petitions calling for an end to testimony laws. Their demands didn't get far. Even in California, southern white men from slave holding states maintained a stranglehold on just about every branch of government. Still, the Colored Convention delegates left behind an important record of Black Californians relentless battle for full citizenship rights. But the just society they fought for wouldn't arrive soon enough to help George Gordon.

Frances Kaplan: [00:08:51] So this is our first locked door. I'm just going to swipe the entrance.

Tammerlin: [00:08:54] At the California Historical Society in San Francisco, archivist Frances Kaplan oversees the library's collections. Many of the papers it stores are fragile.

Frances: [00:09:08] And we always use rolling carts to carry the materials because it's so much more stable, even if it's just a photograph or one box or one item.

Tammerlin: [00:09:21] We wait for an elevator to take us where the society stores manuscripts in temperature controlled vaults.

Frances: [00:09:31] And we're on our way.

Tammerlin: [00:09:34] The elevator opens into a dim, narrow room, with rows upon rows of metal shelves nearly floor to ceiling. They hold acid free archive boxes.

Frances: [00:09:47] What we are looking for is. This one here! Petition for the legal recognition of Black Californians circa 1852 to 1862.

Tammerlin: [00:10:02] Kaplan places a cream colored folder onto a soft foam stand.

Frances: [00:10:07] It holds the paper at an angle, so it's easy for us to read, but we're not having to hold it.

Tammerlin: [00:10:14] Inside, neat cursive writing covers three blue lined pages. There are portions where the writer fix mistakes as they went along.

Frances: [00:10:22] On the third page where the petitioners names would normally be or the signatures, it has been cut and it doesn't look like a rip, it looks like it actually has been purposely cut.

Tammerlin: [00:10:35] There's a lot. The California Historical Society doesn't know about the document, like where it came from or how it ended up in its archives or who wrote it, and whether he intended this document to be a draft. Kaplan says she's not even sure whether the writer ever sent it. But she's pretty confident that someone Black wrote it between eighteen fifty two and eighteen sixty two during the long campaign to end the testimony laws.

Frances: [00:11:04] It's addressed to the honorable the Senate and Assembly of the state of California.

Petitioner: [00:11:11] That said statutes are unjust and oppressive, both to the white and the black. That crime often goes unpunished for the reason that the only witnesses to its commission or persons disallowed by these statutes from testifying.

Frances: [00:11:31] Your petitioners are of opinion that judges and jurors ought to be allowed to judge of the weight, which should be given to evidence of colored persons, and that they should be as capable of determining whether a Black man is speaking the truth as a white man. One of the things that is so incredible about this document is that it was written about African-American civil rights by African-Americans. I mean, I'm presuming.

Tammerlin: [00:12:01] It's the kind of petition that delegates to the Colored Conventions were writing,

Frances: [00:12:08] There's just not that many documents that we have in our collection that are like that.

Tammerlin: [00:12:14] It's been digitized, so it's available online to the public. We can only imagine who wrote this fragile document that somehow managed to survive for all we know. George Gordon might have helped draft it.

Frances: [00:12:33] It's hard to believe we're so close to where George Gordon was actually murdered.

Tammerlin: [00:12:40] The intersection of California and Sansom streets lies in the heart of San Francisco's financial district. Today there's a Bank of California here, but in the 1850s, George Gordon's time it was a three-story hotel called Tehama House. It attracted the city's political movers and shakers, and many of those gentlemen formed Gordon's clientele at the barbershop he ran in the basement. On an autumn Tuesday morning, George Gordon is at work. A few customers wait for shaves and haircuts. Around 10:30. A man named Robert Schell walks in with two other white men and heads straight for Gordon. He shouts that "affair last night was not quite right." George Gordon replies,

George Gordon : [00:13:30] Yes, it was. You went down on the money.

Tammerlin: [00:13:33] Schell showed up to confront the barber because of something that had happened the night before. Gordon's wife had reported the white man to the police. She said he'd walked into her hat shop when he thought no one was looking and stole $11 from the cash drawer when the police questioned him. He flew into a rage at the notion that a Negro would accuse him of a crime. At the barbershop, Schell gets physical. He starts pummeling George Gordon with a cane. When the men grab each other, two customers rush over to pull them apart as soon as they separate. Schell pulls a Derringer pistol and shoots George Gordon in the chest. He staggers out onto the street and Shell chases him to continue his vicious attack in full view of witnesses. George Gordon's funeral took place two days later at his home on Minna Street. There, the mortician's records note, he was laid out in a rosewood coffin. Black, Chinese and white San Franciscans gathered as two coaches accompanied a horse drawn hearse to the Lone Mountain Cemetery. A prominent white minister delivered the eulogy. One newspaper described George Gordon as a man of intelligence who had a handsome property. He was 34 years old when Robert Schell killed him. The coroner's report, newspapers and historians have written about the case. Although the details differ slightly, the basic story is the same.

Tammerlin: [00:15:14] There was no doubt that Schell murdered George Gordon, an unarmed man in cold blood. But in order to convict him of first degree murder, the prosecution had to prove his racist intent in court. The problem was most of the customers in the barbershop were black. That meant they couldn't testify. That left the prosecution with one white eyewitness, or should we say, someone who identified as white? James Cowls was light skinned with what one reporter described as a wig of straight hair. The witness said he was from Portugal, but Shell's defense attorney challenged Cowls' testimony on the grounds that he was a Black man. That would have prohibited Cowls from testifying against his client. In the crowded courtroom as spectators watched, the judge ordered Cowls to undergo a physical examination. Southern doctors who claimed expertise in racial science examine Cowls' eyebrows with a microscope. They concluded based on what they called an unmistakable kink in his hair, that the witness was black. So the judge wouldn't admit Cowls' sworn testimony. That left the prosecution with no witnesses to the shooting. A white witness testified that he had seen Schell beating Gordon in the street. As a result, the court convicted Schell of manslaughter instead of murder.

Pacific Appeal Newspaper: [00:17:04] The trial of Schell for the murder of George W. Gordon, the colored barber on the 29th of October last was a complete mockery of justice.

Tammerlin: [00:17:16] The Pacific Appeal, a black newspaper, published this assessment.

Pacific Appeal Newspaper: [00:17:21] The fact is well known that it was one of the most deliberate and cold blooded murders that has ever disgraced California, even in her rudest and most lawless days,

Tammerlin: [00:17:34] White newspapers that rarely mention black lives or deaths also reported on George Gordon's killing. The news made it all the way to the East Coast, from where he'd moved in search of better opportunities only to meet a violent demise, says historian Clarence Caesar.

Clarence: [00:17:53] Once word got out of the conditions surrounding the George Gordon case, East Coast newspapers basically started saying, well, what's going on in California? You know, this is supposed to be a state of opportunity for African-Americans and blacks. And yet this is a black man who was murdered with impunity for trying to protect his wife and their property.

Tammerlin: [00:18:14] The publicity embarrassed white San Franciscans. Some in the legal profession lobbied to repeal the testimony laws. So George Gordon helped to compel change, even though he wasn't alive to see it. We don't know what happened to his wife and their son. A year after Gordon died, the San Francisco City directory lists and Isabella Gordon colored widow, occupation dressmaker. She was living at the same address on Minna Street, where George resided and his funeral was held. Beyond that, official records contain no trace of her. Their lives mattered, says Clarence Caesar.

Clarence: [00:19:05] Despite the fact that a lot of what they accomplished in the conventions wasn't realized until the Civil War was in effect, it still shows that they had enough moxie, gall and smarts to thrive even in the worst conditions in California, and they left a legacy for all of us to follow in modern times.

Tammerlin: [00:19:27] The law no longer keeps African-Americans from testifying against white people in legal actions, but that exclusion didn't just go away.

Amanda Carlin : [00:19:37] Starting with the formal exclusion of slaves and then of freed slaves and Black people, generally all of the actors in the courtroom were white. So the courtroom developed as this distinctly yet invisibly white space.

Tammerlin: [00:19:54] Amanda Carlin is a Los Angeles attorney who represents formerly incarcerated people re-entering society. When she was a law student at UCLA, she researched the 19th century testimony laws. Her purpose to examine what she calls an invisible baseline of whiteness that helps define acceptable court behavior. Because of that baseline, Carlin says,

Amanda Carlin : [00:20:20] Truth developed as distinctly white because the only people that ever spoke legal truths were white because everyone in the courtroom was white.

Tammerlin: [00:20:29] A system built on the foundation of those laws was hardwired from the beginning to discredit the sworn word of anyone who is not white.

Yoel Haile: [00:20:38] They are not allowed by law to say You are Black. You can't serve on a jury. They used to do that. They can't do that anymore.

Tammerlin: [00:20:46] Yoel Haile heads the criminal justice program at the ACLU of Northern California. He says that while attorneys can't legally dismiss potential jurors based on race, they manage to do it anyway.

Haile: [00:21:00] The prosecutors in the defense get a set number of what are called peremptory challenges, where either side can kick you out of serving on a particular jury.

Tammerlin: [00:21:10] The attorneys aske potential jurors questions that sound neutral. Do you support Black Lives Matter? Have you or anyone you know, ever had a negative experience with the police officer? Common tactics to screen out people of color?

Yoel: [00:21:28] If the defendant is white and especially if the defendants are white supremacists or police officers, the prosecution calculation is that they know that if there is Black people or people of color on that jury, those people are going to bring their experiences with law enforcement into the jury deliberations.

Tammerlin: [00:21:49] This doesn't only happen in California, in 2021, three white men stood trial for murdering Ahmaud Arbery, who is Black as he jogged through a neighborhood in South Georgia. Shielded by the local prosecutor, Arbery's killers remained free for several weeks. Glynn County Police didn't arrest them until cell phone video of the killing went viral on social media. The suspects' attorneys used peremptory strikes to remove all but one of the Black potential jurors.

News Report: [00:22:25] In a county whose population is nearly 30 percent Black, the judge in the case said there appeared to be intentional discrimination on the part of the defense, but said he did not have the legal authority to do anything about it.

Tammerlin: [00:22:39] Given the history in the South, news reports noted people had good reason to be concerned whether justice would be served in Arbery's killing.

News Report: [00:22:48] We have a case in which an African-American man was hunted down and killed by three white men. Those men have been charged with a number of crimes, including murder, false imprisonment and aggravated assault, and now they have virtually an all white jury.

Tammerlin: [00:23:10] Well, when that jury convicted the three men of murder, some people said the verdicts proved that the criminal justice system works. But those convictions almost didn't happen. We have made progress, but we're still a long way from the just society that George Gordon was fighting for. You've been listening to gold chains, a production of the ACLU of Northern California.

Tammerlin: [00:23:42] I'm your host and writer. Tammerlin Drummond. Cheryl Devall edited this episode. Renzo Gorrio created the mix and original score. We'd like to thank voice actor Steven Jones, along with the commentators and guides you heard in this story. Dean Hassan, as well as Gold Chains team members Brady Hirsch and Steven Wilson, lent their voices. Thanks to Candice Francis, our ACLU communications director and the rest of our Gold Chains team, Carmen King, Gigi Harney, and Eliza Wee. Thank you also to Abdi Soltani, our executive director. The San Francisco Public Library and the California Historical Society assisted with our research. Visit Gold Chains: The Hidden History of Slavery in California at GoldChainsCA.org. It includes links to our guests in this episode and to other narratives, including the digital Colored Conventions project. If you like what you've heard, please rate it wherever you listen and spread the word. Thank you for listening.

The mission of Gold Chains is to uncover the hidden history of slavery in California by lifting up the voices of courageous African American and Native American individuals who challenged their brutal treatment and demanded their civil rights, inspiring us with their ingenuity, resilience, and tenacity. We aim to expose the role of the courts, laws, and the tacit acceptance of white supremacy in sanctioning race-based violence and discrimination that continues into the present day. Through an unflinching examination of our collective past, we invite California to become truly aware and authentically enlightened.